Sustaining Essential Health Services during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Social Imperative

Patricio V. Marquez, Huihui Wang, Lydia Ndebele

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic is currently affecting 188 countries and territories across all regions. In all but a handful of countries, COVID-19 exploited weaknesses across health system platforms, pointing out strong need for resilient health systems. Under-resourced surveillance platforms were unable to promptly detect community spread until viral circulation was already widespread. Insufficient stockpiling, contingency planning, and coordination across regional, national, and international public health platforms led to shortages of essential supplies and equipment, sparking bidding wars and leaving health workers without appropriate protective gear. Hospital platforms were overwhelmed and stressed beyond capacity, with fragmentation hampering the efficient flow of patients, staff, and equipment.

For countries that had weaker health systems and less resources, the impact can be both significant and long-lasting. COVID-19 may affect countries’ journey to Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goal 3 through several pathways:

1. Increased morbidity and mortality directly attributed to COVID-19

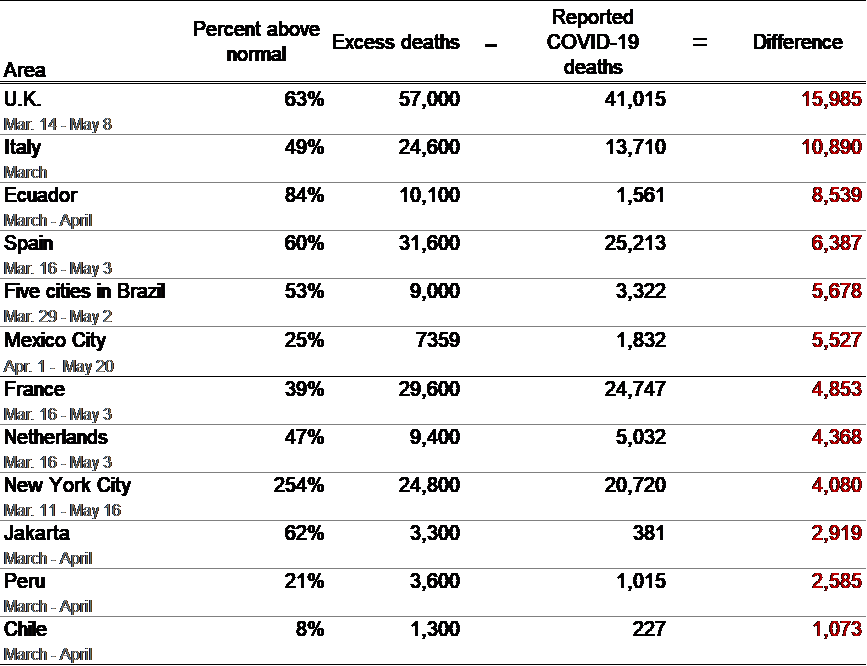

- As of June 16, 2020, there have been close to 8 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and more than 434,000 deaths (JHU&M 2020). Since testing capacity lags in most countries, the number of new cases is likely to be underestimated. Similarly, mortality data should also be interpreted with caution, as many countries show significant underreporting of COVID-19- related deaths (Table 1). Differences in data collection, as well as delays in death registrations, contribute to the problem.

- Unexplained deaths provide a proxy for underreporting. They are estimated as the difference between observed deaths and the projected number of deaths based on historical and seasonal trends. The difference may be attributed to COVID-19 or to other factors, such as a shortage or lack of essential medical services for other conditions. While it is not possible to know the true death toll of COVID-19, it is clear that in some countries daily deaths have reached rates 50% or higher than the historical average for periods of time.

Table 1. COVID-19 underreported deaths

Source: For all cases, except Mexico, The New York Times “74000 missing deaths: tracking the true toll of the coronavirus outbreak.” Updated May 19. For México City Nexos: “¿Qué nos dicen las actas de defunción de la CDMX?”, May 25, 2020.

- Based on currently available information and clinical expertise, older adults and people of any age who have serious underlying medical conditions might be at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19 (CDC 2020), particularly those with weakened immune systems. People with chronic lung disease or moderate to severe asthma, serious heart conditions, who are immunocompromised (many conditions can cause a person to be immunocompromised, including cancer treatment, smoking, bone marrow or organ transplantation, immune deficiencies, poorly controlled HIV or AIDS, and prolonged use of corticosteroids and other immune weakening medications), severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 40 or higher), diabetes, chronic kidney disease undergoing dialysis, and liver disease. Conditions such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, are already among the ten leading causes of premature death in the world, accounting for more than 1 million deaths each in 2017 (IHME 2018).

- As the first country to be impacted, China’s reported data provides insights into the biology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 (Guan, Ni, Hu, Liang, et al 2020). A higher prevalence of smoking among men, often resulting in compromised lung function, may help explain their higher COVID-19 fatality rate. Tobacco use also contributes to the onset of co-occurring conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, COPD, and diabetes, which are more prevalent among males, and which also increase the risk of disease severity and death among COVID-19 patients. Data from Italy also shows that a high proportion of COVID-19 patients had a history of smoking and high rates of COPD and heart disease (Boccia, Ricciardi, Ioannidis 2020). The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is also facing an increased pressure on health systems from COVID-19 (coronavirus), with over 200,000 confirmed cases and almost 10,000 deaths reported, on top of a high and growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (Duran and Menon 2020).

- Sub-Saharan African countries can be potentially hit hard with a large number of people are at higher risk of infection due to preconditions: about 26 million live with HIV and 2.5 million fall ill from tuberculosis annually, while South Africa and Namibia have high mortality rates from NCDs (Marquez and Farrington 2013). As experienced by some high-income countries, people in low- and middle-income countries (especially the poor) may refrain themselves seeking care or getting tested due to financial barriers, which in turn will worsen the pandemic.

- Simultaneous epidemics are overwhelming public health systems in different countries that had few resources to begin with. In some countries, the threat of dengue fever is being taken as seriously as COVID-19. For example, in Central America, Honduras has seen a steep climb in COVID-19 cases in the midst of a dengue fever outbreak. San Pedro Sula, the business capital where gang violence makes Honduras one of the deadliest countries in the world, is also now the epicenter of a COVID-19 outbreak (Gannon 2020). In Singapore dengue infections may for 2020 exceed the all-time high of 22,170 set in 2013 (Goodman 2020), while in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul in Brazil, health authorities are dealing with additional dengue fever cases, bringing the total this year so far to 61,604 confirmed cases. (Newsdesk 2020). In Pakistan, the country’s toll of above 139,000 coronavirus cases surpasses that of neighboring China with 84,000 confirmed cases, and more than 2,600 people in Pakistan have already died. At the same time, Pakistan continues to suffer some of the world’s worst outbreaks of infectious diseases, with 4.3 million cases of malaria annually, and is also one of the top 10 countries for new cases of tuberculosis each year, and is one of only three countries, including Afghanistan and Nigeria, where polio is still endemic (Gannon 2020). Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a new outbreak of Ebola in Equateur Province is now compounding the public health challenge posed by COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 4,000 confirmed cases reported (Schlein, 2020).

2. Increased morbidity and mortality due to interruption of essential service delivery associated with COVID-19 containment measures

- During the 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, it was observed an upsurge in mortality and morbidity from other diseases and conditions (Bietsch, K, Williamson, J, and Reeves M. 2020; Camara BS et al. 2017; Hall KS et al. 2020; Sochas, L, Channon, AA, and Nam, S. 2017), and this is happening again during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shortage of health workers is exacerbated as many of them are diverted to managing COVID-19 cases, or hampered by lack of protective gears, or advised to discontinue service delivery. Local or national lockdowns, along with the consequences of physical distancing, travel restrictions, disruptions on the supply chain for contraceptive commodities, and the fear of health facilities among pregnant women, may risk undermining or reversing the progress made in the past decade to improve the access to and quality of sexual and reproductive health services and reduce unwanted teenage pregnancy and maternal mortality. Consequently, women and children are affected disproportionately, especially those living in fragile contexts. For example:

- Increased unmet need for modern contraceptive: Initial estimates show that a 10% proportional decline in use of short- and long-acting reversible contraceptive methods in LMICs due to reduced access would result in an additional 49 million women with an unmet need for modern contraceptives and an additional 15 million unintended pregnancies over the course of a year ((Riley, Sully, Ahmed, and Biddlecom 2020).

- Additional maternal and newborn deaths: An additional 1.7 million women who give birth and 2.6 million newborns would experience major complications but would not receive the care they need, resulting in an additional 28,000 maternal deaths and 168,000 newborn deaths (Riley, Sully, Ahmed, and Biddlecom 2020).

- Wide-spread interruption of immunization program: A recent report by WHO (2020) indicates that since March 2020, routine childhood immunization services have been disrupted on a global scale that may be unprecedented since the inception of expanded programs on immunization (EPI) in the 1970s. More than half (53%) of the 129 countries where data were available reported moderate-to-severe disruptions, or a total suspension of vaccination services during March-April 2020. Many countries have temporarily suspended preventive mass vaccination campaigns against diseases like cholera, measles, meningitis, polio, tetanus, typhoid and yellow fever, due to risk of transmission and the need to maintain physical distancing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Measles initiatives, for example, have been suspended in 27 countries, including Chad and Ethiopia, and polio programs are on hold in 38, including Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Hoffman 2020). The problem of slipping vaccine rates is not limited to developing countries. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported drop in visits and fewer vaccine doses being administered in the United States, leaving children at risk for vaccine-preventable diseases (Santoli, Lindley, DeSilva, et al 2020).

- Transport delays of vaccines are exacerbating the situation. UNICEF has reported a substantial delay in planned vaccine deliveries due to the lockdown measures and the ensuing decline in commercial flights and limited availability of charters (UNICEF 2020). This particularly affects countries in FCV areas where immunization delivery relies heavily on community outreach and campaign programs most of which are put on hold due to social distancing requirements. As a result, at least 80 million children under one at risk of diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio as COVID-19 disrupts routine vaccination efforts (WHO 2020, 1).

- In addition to physical health, mental health for all and especially the displaced also needs to be prioritized. COVID-19: Exposed by the coronavirus crisis, everyone is affected mentally through losses such as the death of loved ones, illness, diminished life’s savings, or in being confined, having to forgo life’s significant occasions, transitions, plans, or experiences. For displaced communities – for example refugees or asylum seekers – the mental health fallout will be significantly more acute, while their access to health care reduces (Marquez 2017). In Afghanistan, for example, which is in the midst of a displacement and refugee crisis (more than 400,000 IDPs; 505 000 refugees returning from Iran), one can anticipate a rapid exacerbation of these challenges (Pierre-Louise 2020). To restore economic activity in the aftermath of the pandemic, besides financial and physical well-being efforts are needed to address mental health of individuals and communities.

3. Uncertain financing prospects for health system accompanied by growing demand to look after the poor

- While countries are mobilizing all potential resources for health system to fight against the pandemic, the negative impact on countries’ macroeconomic situation might cascade down to health system. Indeed, World Bank estimates indicate that as many as 90% of the 183 economies are expected to suffer from falling levels of GDP in 2020. Tighter fiscal space and shrinking revenue for employment-based insurance schemes may enlarge the financial gap for investing in health. Furthermore, the World Bank estimates that under a baseline scenario with global growth contracting by about 5% in 2020, and downside scenario with a global growth contraction of 8% in 2020, COVID-19 will push 71 million into extreme poverty, measured at the international poverty line of $1.90 per day (Gerszon Mahler, Lakner, Castaneda Aguilar, Wu 2020). With the downside scenario, this increases to 100 million people.

- These scenarios pose significant financing challenges for ensuring population access to essential services. If not well managed, countries may be pushed to a situation in which the relative importance of out-of-pocket payments may rise, a mechanism deemed most inequitable and least efficient, and that poses a high risk of impoverishment to the population. Even before the pandemic, the incidence of catastrophic health expenditure (SDG indicator 3.8.2), defined as large out-of-pocket spending in relation to household consumption or income, increased continuously between 2000 and 2015 (WHO/WBG 2020). In 2015, 926.6 million people incurred out-of-pocket health spending exceeding 10% of their household budget (total consumption or income), and 208.7 million incurred out of pocket health spending that even exceeded 25% of the household budget (WHO/WBG 2019). These people lived mostly in Asia (70%–76%), about 45% in lower-income countries and 41%–43% in upper-middle-income countries. Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest percentage of their 2015 population with catastrophic health spending as tracked by SDG indicator 3.8.2, while North America and Oceania had the lowest.

- In 2015, out-of-pocket health spending contributed to pushing more people below the poverty line: 89.7 million people (1.2%) were pushed into extreme poverty (below $1.90 per person per day in 2011 purchasing power parity terms), while 98.8 million (1.4%) were pushed below $3.20 per person per day and 183.2 million were pushed into poverty defined in relative terms (below 60% of median daily per capita consumption or income in their country) (WHO/WBG 2019).

4. What to Do?

As the COVID-19 continues to evolve, it is imperative that countries adopt measures to balance the demands of responding directly to COVID-19, while simultaneously engaging in strategic planning and coordinated action to maintain the delivery of routine essential health services, mitigating the risk of system collapse (WHO 2020,2). Travel restrictions and lockdowns, people putting off seeking needed health care for any number of conditions from fear of becoming infected with COVID-19 in a health facility, disruptions in the global supply chain of essential personal protective equipment, medicines and medical materials, demand solutions beyond the usual way of operating to be able to continue caring for patients affected by concurrent conditions.

To ensure continuity of routine essential health services to meet all the health needs of the population, innovative approaches have been launched in different countries. Some of them are presented below.

- Use of family medicine and integrated networks at all three levels of care, as done in Costa Rica (Macaya 2020), as well as in Cuba and in the Kerala State in India, where the whole organization of the health care system is geared to be in close touch with the population, identify health problems as they emerge, and deal with them immediately along a care continuum (Augustin 2020; Shailaja, K.K., Teacher, and Khobragade, RN, 2020). In these countries, the primary health care system acts as the entry point to the integrated health system, facilitating early identification and timely referral of cases to higher levels of care for appropriate management.

- Improving the equity of health financing and service delivery. Available data from the United States show the estimated average cost for possible procedures that might occur for COVID-19 treatment and the significant disparity between people with health insurance and those who lack insurance or have limited access to publicly-funded health services. For people with health insurance who have met the required deductible, they would need to pay only the co-pay or co-insurance, while the insurance plan would pay the remaining balance. In the case of people without insurance, they would have to pay 100% of the price of COVID-19-related medical costs, which could set a patient and his/her family back financially (Abrams 2020). While health systems, financial protection arrangements, and medical cost structures vary from country to country, it should be clear that in countries without universal health coverage, the financial impact of COVID-19 on the population, particularly low-income groups, could be significant or even catastrophic if adequate provisions are not taken to offer financing protection to the population. In the MENA region, for example, to mitigating the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19, particularly for the most vulnerable populations, the elimination of user fees and copayments has been proposed for all health services (Duran and Menon 2020).

- Drone delivery is changing the face of global logistics. The experience in Rwanda’s health system is noteworthy. Beginning in 2017, Rwanda, in partnership with California-based robotics company Zipline International Inc., became the first country in the world to incorporate drone technology into its health care system for delivering blood and medical supplies to hospitals across its Southern and Western provinces (Marquez 2019). Establishment of drone delivery systems for transporting samples from remote areas to test centers during the COVID-19 pandemic has also been initiated in Ghana, alongside the distribution of drugs and blood products (Nsiah Asare 2020).

- Increasing the availability of telemedicine for ambulatory services. This use of this technology helps to provide online infection prevention and control trainings for care home workers, running health promotion campaigns on social media, to managing WhatsApp groups of traditional healers (MSF 2020). Telemedicine can play a critical role in ensuring that patients continue to receive non-urgent care, particularly those with chronic conditions.

- Engagement of community health workers and mobile health teams. To minimize the negative impact of the reduction of recommended number of antenatal consultations for pregnant women in clinics, the engagement of trusted people in their communities is critical to ensure that women can still receive the care they need. Community personnel can help identify when a woman needs to go to hospital because of complications (MSF 2020), or help organize service delivery by mobile teams, particularly to cover hard to reach rural areas.

- Distribution of essential drugs to patients for longer periods (one to six months depending on the person’s health condition) so that they do not have to visit a health facility as often for follow up care for HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis C and non-communicable diseases. At the same time, measures adopted to ensure that patients receive follow-up through phone consultations, messaging apps and peer support networks (MSF 2020).

- Use of smartphones for ‘video observed therapy’, for example for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), so they can film themselves taking their medication and send the video to be checked by a nurse (MSF 2020).

- Use of telephone hotlines for the provision of consultations by counselors and psychologists for patients with mental disorders. This approach also helps to reduce the fear of stigma and discrimination that hinders service demand and utilization (MSF 2020).

- Planning efforts are needed to ramp up vaccinations for every missed child when the pandemic Covid-19 ends, and to make advance provisions to ensure that when the COVID-19 vaccine is available, it reaches those most in need.

- Looking into the future, the global spread of COVID-19 clearly signals the need, hopefully once and for all, for building and maintaining strong and sustainable public health and medical institutions and systems in countries. This needs to be complemented by effective cross sectoral interface between environment, veterinary and public health services to anticipate, prevent, and control the emergence of new infectious pathogens of animal origin, the resurgence of known infectious diseases, and the ominous threat of anti-microbial resistance. This task is of priority importance where health systems are weaker, living conditions often more overcrowded, and populations most vulnerable.