Safe Water and Basic Sanitation: Critical Investment for Safeguarding Public Health and the Ecosystem in the Galapagos Islands--A World Heritage Site

Patricio V Marquez

January 17, 2024

“I will impart to you a discovery of a far wider scope than the trifling matter that our water-supply is poisoned.”

---Henrik Ibsen

“An Enemy of the People” (1882)

“This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s a matter of common decency. That’s an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of fighting a plague is--with common decency.”

--Albert Camus

“The Plague” (1948)

Background

At the end of 2023, the Ecuadorean press reported on the serious sewage and drinking water problems in Santa Cruz--one of the few inhabited but most populous island in the Galapagos Archipelago. The local authorities cited in the press articles claimed that the sewage system is non-existent and that wastewater, which is filtered, goes into a crevice or underground, asserting that it could be contaminating the water consumed by the population. This problem is exacerbated by increasing pressure on the solid waste management system due to the growing resident population and tourists, as well as the influx of plastic waste from continental Ecuador and neighboring countries being washed onto pristine beaches and shores by powerful ocean currents.

The scenario depicted by the local authorities merit attention as it highlights a grave challenge not only to Ecuador but also to the global community in their efforts to preserve the unique and fragile ecosystem of the Galapagos Islands, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A limited supply of clean water, untreated wastewater, and the escalating problem of solid waste and plastic pollution pose not only public health risks but also are substantial threats to the welfare of both marine and land animals, as well as the overall ecosystem in the Galapagos Islands.

Here I delve into some of the reasons for this concern based on a review of available information and explain why it should matter to all of us.

Galapagos: A UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site that Needs to be Preserved

When travelling to the Galapagos Islands, an archipelago consisting of 13 major islands, 6 smaller islands, and scores of islets and rocks located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, west of Ecuador’s mainland, one discovers that the observations made by Charles Darwin when visiting the islands in 1835 have in large measure withstood the passage of time. While there are scarce remains of visits by pirates, buccaneers, and whalers from the late 1500s through the early 1800s, and later of repeated, but failed, colonization attempts by penal colonies and settlers, the archipelago continues to be, as observed by Darwin, “a little world within itself, or rather a satellite attached to America, whence it has derived a few stray colonists, and has received the general character of its indigenous productions.”

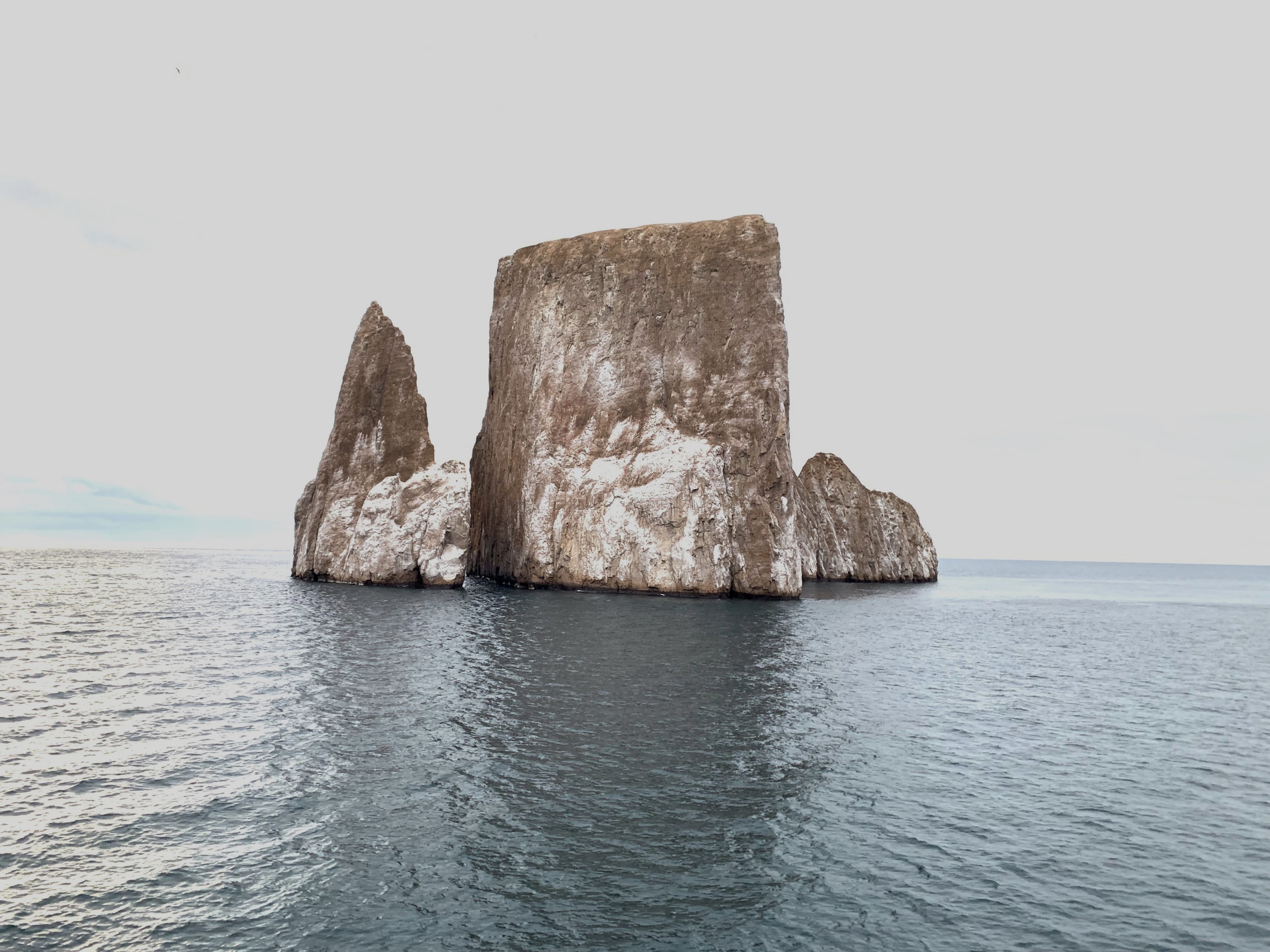

The geological formations in the islands combine rocky stretches of shoreline, pristine beaches with sand of diverse colors, active volcanoes, verdant highland regions, and patches of red Sesuvium, a plant that adds color to the uninhabited areas. Beautiful, isolated rock outcroppings such as the León Dormido (“Sleeping Lion”), facing San Cristobal Island, offer a dreamlike view at sunset. And “in vivo” geological forces, such as the marine reef off the coast of Urbina Bay that was uplifted by as much as fifteen feet, are a testament to unrelentless volcanic forces, oceanic currents, and trade winds that shape the islands.

The unique fauna of the Galapagos Islands, which transports us to another era in time, stimulated “the origin” of Darwin’s ideas about evolution. Indeed, his observations first recorded in 1835 in his journal “The Voyage of the Beagle”, underpinned his seminal work, “On the Origin of Species”, published in 1859, that changed the scientific understanding of the natural world by putting forward his theory of “descent with modification.”

The richness of the species that inhabit the Galapagos Islands, “peculiar to the group” and some “found nowhere else”, include the blue- and red-footed boobies, frigate birds, and several species of finches in different islands. Other species, like the American flamingo and land iguanas, have a more restricted distribution, and some species are restricted to just one island, such as the waved albatross, that nests exclusively on the Española Island, and the flightless cormorant, found only on Isabela and Fernandina Islands. The “saddle-shaped” giant tortoises, iconic species of the archipelago, with an average life expectancy of close to 200 years, move between the highlands and dry zones, depending on the island and season. The wildlife at sea includes cold-water penguins, green sea turtles, marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, and Sally Lightfoot crabs, along with many species of sea and shore birds. There is also a rich and diverse underwater world, nurtured by diverse ocean currents that converge on these remote shores, including tropical-reef fish, whales, dolphins, and a variety of shark species, including white-tip, and hammerhead sharks.

The Government of Ecuador designated part of the Galapagos a wildlife sanctuary in 1935, and in 1959 the sanctuary became the Galapagos National Park. In 1978 , UNESCO declared the Galapagos a Natural World Heritage Site for Humanity, and the Galapagos National Park a Biosphere Reserve in 1984. In 1986, the Galapagos Marine Resources Reserve, covering 133,000 sq km, was created to protect the surrounding waters. Later in 2001, UNESCO extended the World Heritage Site designation to include the Galapagos Marine Reserve. In 2021, at the COP 26 climate summit in Glasgow, Ecuador announced that it was expanding the marine reserve around the Galapagos islands by 60,000 sq km.

About 25,000 people inhabit four of the 13 large islands in the archipelago (San Cristobal, Santa Cruz, Isabela, and Floreana), making a living from tourism, fishing, and farming. In 2022, 267,688 tourists visited Galapagos. While Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, on San Cristobal Island, is the capital of the Ecuadorian Province of Galapagos, over half of all Galapagueños live in the town of Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island, which is the center of tourism and conservation, as well as the homebase of the Charles Darwin Foundation, the oldest nonprofit research institution in the Galapagos, that serves as the primary partner of the Galapagos National Park, conducting research and capacity-building support to aid in the conservation efforts for the sustainable development of the islands.

Safe Water Supply Challenges

Data from latest census conducted by Ecuador’s National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), shows that in 2015 more than three-quarters of the households obtained water through piping inside the dwelling, an increase of 16.1 percentage points compared to the 2010 census. Meanwhile, 8.9 percent of households were supplied with water through piping outside the dwelling but within the building or property, and 5.1 percent of households did not receive water through piping but through other means. Regarding the water supply source, 89.9 percent of Galapagos’ households in the 2015 census primarily obtained water from the public network, followed by water delivery trucks (3.9 percent), from a river, spring, ditch, or canal (0.6 percent), from a well (0.3 percent), and 5.2 percent of households obtained water in other ways (e.g., rainwater/cistern water).

Overall, the inhabited islands of the Galapagos face significant challenges related to their water supply and quality. The population connected to municipal distribution systems receive water for limited time during the day, particularly during the summer months, necessitating use of cisterns (buried or partially buried tanks) or roof tanks (to store treated drinking water so that water is available when needed).

San Cristobal Island has access to surface freshwater from various sources such as aquifers and springs. However, the water provided by the municipal drinking water treatment plant is intermittent due to limited availability. Additionally, this problem is exacerbated by the deteriorating state of the aging pipes within the drinking water system. This situation necessitates household-level water storage, making the system vulnerable to contamination and leading to insufficient residual chlorine concentrations for continued disinfection during storage.

The findings of a recent study indicated that while the municipal water treatment plant in San Cristobal Island generally produced high quality drinking water, the detection of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria in 2–30 percent of post-treatment distribution samples suggested that there was contamination and/or regrowth during distribution and storage. Linear regression revealed a modest, negative relationship between residual chlorine and microbial concentrations in drinking water samples, while 24-h antecedent rainfall only slightly increased microbial counts. While most strains of E. coli, a type of bacteria that naturally resides in the gastrointestinal tract of both humans and animals, are harmless, some strains can make people sick with watery diarrhea, vomiting and a fever.

Moreover, the findings of the study highlighted that the wastewater effluent contained E. coli concentrations that greatly exceeded the Ecuadorian standards and was not suitable for discharge into a marine water body. The beach site receiving the effluent (Punta Carola 1) showed significant declines in water quality, marked by elevated Enterococcus bacteria counts, reduced dissolved oxygen levels, and increased turbidity when compared to other coastal sites. The Enterococcus levels even exceeded the World Health Organization's (WHO) no-observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) of <40 MPN/100 mL, with 89 percent of samples exceeding the WHO standard. The enterococcus bacteria can cause infections in people that are often difficult to treat with ordinary doses of antibiotics.

Two of the other inhabited islands, Santa Cruz and Isabela, struggle with freshwater scarcity, relying on municipal desalination plants to treat brackish (salty) water; small-scale, private reverse osmosis water purification plants, for bottled water for consumption; and bottled water purchased at supermarkets. The water distributed to homes and commercial and tourist establishments in Puerto Ayora is still brackish and not suitable for human consumption and limited to just a few hours a day. Typically, all buildings have large storage tanks on the rooftops, and these are filled when the water is running, so that it can be used over the course of the day. The desalination plants face problems, including unreliable functionality in Santa Cruz, and limited storage capacity on Isabela, resulting in drinking water out of compliance with international standards.

The results of the above-mentioned study in San Cristobal underscored the challenge of providing a safely managed drinking water source where limited freshwater quantities result in intermittent flow and require storage at the household level. The key policy making implication from this study, therefore, is that in designing these systems in the Galapagos Island it would be important to ensure the supply of safe water all the way to the point of use. Unless reliable desalination plants are installed to increase the water supply, the Galapagos Islands' ongoing water quantity challenge, exacerbated by tourism growth, is likely to persist. This implies that efforts to enhance water quality in the Galapagos Islands should concentrate on distribution and storage, with a particular emphasis on maintaining sufficient chlorine levels and keeping cisterns and roof tanks clean. Properly managed neighborhood-level cisterns that deliver high-quality water to households could be a potential part of the solution.

Sewage Facilities and Services Challenges

According to the 2015 INEC census, 72.3 percent of households in Galapagos had a hygienic toilet or latrine connected to a septic tank, followed by 26.8 percent with a hygienic toilet or latrine connected to the public sewer system, less than 1.0 percent were connected to a cesspool or outhouse, and 0.5 percent corresponded to households that did not have a hygienic toilet or latrine.

The sanitary sewage system in the Galapagos Islands poses a significant environmental concern, as untreated sewage could pollute the marine environment, harming the diverse aquatic life. The situation on San Cristobal Island illustrates this problem, where an antiquated sanitary sewage system, installed over four decades ago and well past its operational use life, is compounded by the absence of stormwater sewage network, that leaves the island vulnerable to flooding, erosion, and pollution when heavy rains occur.

In Santa Cruz, as documented in a study, a substantial rise in fertilizer usage in rural areas, coupled with an increase in water demand, particularly in urban areas, has resulted in pollution of both surface water and groundwater. This pollution is primarily due to consistent spills that are inadequately treated by septic tanks. In this Island, the second largest and most populous island in the archipelago, most wastewater is not reprocessed due to the absence of a centralized treatment plant. As a result, this untreated wastewater (water containing organic matter, microorganisms, and inorganic compounds, as well as storm runoff, as harmful substances wash off roads, parking lots and rooftops), either seeps into the lava rock and porous subsoil, ultimately making its way into the sea, or it is directly discharged into the Pacific Ocean.

This endangers not only the scarce freshwater resources for the people in the Island, but also endangers sea animals---more than 500 species of fish, including over 50 species of shark and ray, mussels, snails and starfish, as well as turtles and sea iguanas, sea lions, seals and marine birds, which are exposed to the environmental pollution caused by untreated sewage.

To address this issue, some measures have been taken in populated areas, including the installation of a centralized wastewater treatment plant in San Cristobal Island, and decentralized wastewater treatment units in Santa Cruz Island, as part of a pilot project for sustainable water management supported under the develoPPP.de programme of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (KFW). Regulations on boating and tourism operations have also been adopted requiring vessels to have sewage holding tanks and dispose of waste responsibly when in the waters of the Galapagos.

The implications of failing to improve the sewage system are clear and far-reaching. First and foremost, there is the looming threat of waterborne diseases. Untreated wastewater can harbor dangerous pathogens, capable of causing cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. People with underlying health conditions or a weakened immune system are more likely to get sick when exposed to the E. coli and enterococcus bacteria. The public health risk is evident, with the potential for increased morbidity and mortality rates. Even the risk of antimicrobial resistance looms large, with antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria present in untreated wastewater, adding to public health crisis risks.

The toll on the ecosystem is equally severe as untreated wastewater contaminates coastal areas and water sources. Harmful substances, including heavy metals and chemicals, disrupt aquatic ecosystems, leading to the death of marine organisms, harmful algal blooms, and the degradation of precious coral reefs. This not only endangers marine life but also threatens the livelihoods of communities dependent on fisheries. Land animals and terrestrial ecosystems are not spared either. Contaminants from wastewater can seep into the soil, impacting plant growth and soil quality. Animals that rely on clean water sources for drinking and habitat face reduced access to suitable environments and increased exposure to pollutants.

The risk of antimicrobial resistance is particularly ominous, with anthropogenic activities driving the spread of resistance. In the Galapagos Islands, research conducted by a Charles Darwin Foundation team on Santa Cruz and Alcedo Volcano giant tortoises found antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in both sample populations. However, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the results indicated that Santa Cruz tortoises had higher loads of ARGs compared to those from Alcedo Volcano. Indeed, both qualitative and quantitative results showed that the tortoises inhabiting the human modified environments (farmlands and urban areas) of Santa Cruz, presented a higher number of ARGs, antimicrobial classes, and multi-resistant microbiomes than those from less anthropized areas within the same island. These results suggest that human activities in the Galapagos Islands are negatively affecting the ecosystem by contributing to the spread of ARGs and highlight the need for policy makers to control and reduce the use of antibiotics in both human and animal populations, thus helping enforce antimicrobial regulations.

The consequences extend to environmental degradation, with untreated wastewater contributing to soil erosion, nutrient enrichment in water bodies, and the release of pollutants into the air. The result is a loss of biodiversity, disruption of ecosystems, and habitat destruction.

Beyond these immediate concerns, as explained by Mateus and Quiroga in a recent publication, climate change may exacerbate the challenges posed by growing resident population and tourism, including increasing the amount of untreated wastewater effluents produced on the islands and flushing more of these effluents into the ocean and groundwater and surface water systems, thus degrading water quality.

As noted in a World Bank Group report, wastewater treatment should be considered as a good social and economic investment option to be prioritized as it offers a double value proposition. In addition to environmental and health benefits, wastewater treatment can bring economic benefits through reuse in different sectors. Its by-products, such as nutrients and biogas, can be used for agriculture and energy generation, and additional revenues generated from this process can help cover water utilities’ operational and maintenance costs.

Solid Waste Management and Plastic Pollution Challenges

Accumulated evidence presented in a study suggests that there is a strong linkage between poor solid waste management and environmental/health risks. Examples of environmental and health risks due to waste open burning and open dumping for different waste streams, include: leachate or liquid generated is released to the soil, polluting groundwaters mainly used for drinking and household purposes; the generation of methane and other greenhouse gases increases the risk of global warming, and the risk of local fires and the pollution of the atmosphere surrounding the final disposal sites; and the breeding of animals around the disposal sites and the presence of rodents and insects increases the risks of diseases transferring to the population through bites and direct contact with the animals. In many countries waste is scattered in urban centers or disposed of in open dump sites. The lack of infrastructure for collection, transportation, treatment and final disposal, management planning, financial resources, know-how and public attitude reduces the chances of improvement.

One of the key components of environmental protection, therefore, is the proper disposal of garbage or solid waste. According to the data from the 2015 INEC census, in Galapagos, 98.1 percent of households dispose of garbage through the garbage collection truck, a higher percentage compared to the 2010 census (96.5 percent), while the number of households disposing of garbage by burning account for 1.5 percent of households.

A 2021 report by the Galapagos Conservation Trust (GCT) provides insights into the development of waste management systems on the islands, the challenges faced in maintaining these systems, and potential solutions for the future. Estimates in the report indicate that the cost of waste management in Galapagos has risen significantly, with waste generation increasing by 66 percent from 2010 to 2019--about 12 percent of this waste is estimated to be plastics. As documented in the report, waste management efforts in Galapagos includes the implementation of a 'separation at source' system, starting in Santa Cruz in 2003, followed by San Cristobal in 2007 and Isabela in 2011. This system involves sorting waste into three bins: blue for recyclables, green for organic waste, and black for non-recyclables. Efforts by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Fundación Fundar, have also aimed to raise awareness of the importance of proper waste management and recycling.

But, due to contamination issues, a significant amount of waste still ends up in landfills on the islands, many of which are close to or exceeding capacity, raising environmental concerns. Organic food waste is a significant contributor to waste generation, accounting for over 50 percent of per capita waste in Galapagos. However, many people in the Islands store organic waste in plastic bags, making it unsuitable for composting due to contamination by plastics.

The GCT report suggests that composting solutions for households and collaboration with pig farmers to utilize organic food waste could alleviate the burden on waste management systems. The report indicates that as plastic pollution threatens more than 40 species in the Galapagos Islands due to the risk of ingestion or entanglement, there is now an urgent need to embrace “circular economy” approaches and reduce plastic waste at the source. The concept of a circular economy advocates for a systemic change from the traditional linear 'cradle-to-grave' model to one that emphasizes reducing waste and leakage, following the '4Rs' principle (reduce, reuse, recycle, recover). A practical application of this concept is the newly-launched project by the GCT to support the implementation of measures to prevent local plastic pollution by reducing imports, consumption, and leakage. It also seeks to engage local communities in finding alternatives to single-use plastics while informing sustainable policies and minimizing risks to wildlife in the region.

Despite the ongoing efforts to combat plastic pollution, the Humboldt Current, which flows from southern Chile to Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands, remains a substantial contributor to plastic waste in the Galapagos Marine Reserve (it is estimated that 95 percent of plastic in Galapagos likely to originate outside the Marine Reserve). While this situation presents a formidable challenge that necessitates a more comprehensive and large-scale approach involving collaboration from governments and various stakeholders on national, regional, and global levels, recent research findings highlight the urgent need for measures to address plastic pollution in ecologically sensitive areas. For example, a recent study identified Punta Pitt and Tortuga Bay as hotspots for microplastic accumulation in Galapagos. Both locations are of significant conservation importance. Punta Pitt is home to the only known colony of the rarest subspecies of marine iguana, and Tortuga Bay serves as a nesting site for the Galapagos green sea turtle. Also, the findings of another study indicate that the external adsorption and internalization of plastics by plants and macrophytes raise concerns about the potential entry of plastics into the food web. This has the potential to negatively impact various species, including human food sources, and hence food security.

Takeaways

The preservation of World Natural Heritages sites, such as the Galapagos Islands, depends on the active and dedicated mobilization of support from a broad group of committed stakeholders, both in Ecuador and across the world. If done efficiently and effectively, this effort would help to ensure that the benefits of this global public good will not be limited to the current generations but will also be for the enjoyment of future generations as our lasting legacy to them.

Addressing the water and sanitation services challenges, including plastic pollution, facing the Galapagos Islands is crucial to safeguarding public health and animal health, preserving biodiversity, and maintaining the overall health of the land and maritime ecosystems. Accumulated global evidence presented in a World Bank Group report, shows that there are successful models to reduce wastewater, agricultural runoff, and marine litter, as well as to improve water quality.

It is critical, therefore, to prioritize investments to improve safe water systems and the provision of sanitation facilities and services. There is also an urgent need to raise awareness about these challenges among the resident population and tourists alike and to promote their engagement to ensure the long-term viability and sustainability of the conservation and preservation effort, particularly to anticipate and respond to the risks posed by climate change that threaten to exacerbate stresses on both the natural and built environments.

Looking ahead, the debt-for-nature swap agreement reached in 2023 between the Government of Ecuador and international investors presents a significant opportunity to enhance the scale of conservation and preservation initiatives in the Galapagos Islands. Under this agreement, Ecuador has committed to allocate over US$323 million over approximately 18 years towards these efforts, with a particular focus on the management and monitoring of the Hermandad Marine Reserve, a newly designated protected area announced by the government in 2021. Additionally, a portion of the funds from this transaction will be used to establish an endowment designed to sustainably finance such activities over the long term.

Leveraging some of the funds from the debt-to-nature swap to address the water and sanitation challenges facing the Galapagos Islands should be part of the priority investments that need to be supported. Additional funding sources should be considered to support this effort. As advocated before, based on my previous work at the World Bank Group in different countries, the international experience with ‘health taxes’ levied on cigarettes, vaping products and e-cigarettes, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages could be adapted and replicated in Ecuador, alongside the imposition of a mandatory charge or a tax on single-use plastic carrier bags to carry groceries or other items. Global evidence shows that these type of taxes are a “win-win-win” fiscal policy measure, as they reduce public health and environmental risks by raising prices and lowering the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as discouraging the use of thin, disposable plastic shopping bags to reduce plastic trash, while helping to mobilize additional domestic resources to fund public health and environmental protection programs in national budgets. This measure is of upmost importance in periods of economic austerity as currently facing the Ecuadorian Government and should be included and supported as part of fiscal consolidation efforts to expand fiscal space for these priority investments.

Inaction in the face of the safe water and basic sanitation services challenges will ultimately undermine parallel efforts for the conservation and preservation of the Galapagos Islands. If done effectively over time, we will be contributing to preserve the unique “natural history” of these islands, where, as observed by Charles Darwin in The Voyage of the Beagle:

“Considering the small size of the islands, we feel the more astonished at the number of their aboriginal beings, and at their confined range. Seeing every height crowned with its crater, and the boundaries of most of the lava-streams still distinct, we are led to believe that within a period geologically recent the unbroken ocean was here spread out. Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to the great fact—the mystery of mysteries—the first appearances of new beings on this earth.”

*Source of Pictures: Photos taken by author during visits to the Galapagos Islands, 2019-2023