Social Disparities Among Indigenous Peoples in the Americas: A Legacy to Overcome

The recent social unrest in Ecuador brought to world attention the often ignored and marginalized indigenous peoples that led the opposition to economic reform proposals advanced by the Government. While the unrest ended after some of the proposals were rescinded following a public dialogue between the Government and the leaders of the indigenous movement, deep-seated grievances remain that need to be addressed to improve the social conditions of indigenous peoples.

The situation of indigenous peoples in Ecuador, however, is not different from that in other Latin American countries, as well as in Canada and the United States, each with considerable indigenous populations.

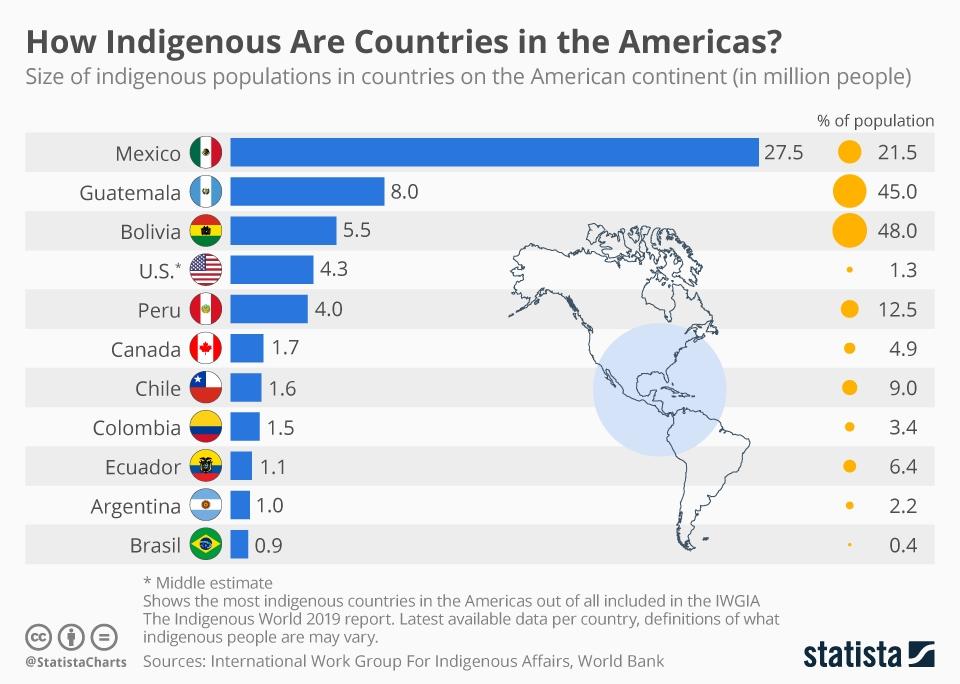

Overall, there are between 45 and 50 million indigenous peoples living in Central and South America and the Caribbean, representing approximately 13 percent of the total population. In the United States, approximately 5.2 million persons self-identify as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and in Canada 1.4 million people self-identify as indigenous. As shown in the graph below, Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, and Guatemala have the largest populations in both absolute and proportional terms, accounting for more than 34 million indigenous people. The indigenous peoples represent more than 400 groups, with 560 diverse languages, cultures, and knowledge systems.

World Bank research has shown that despite the social progress achieved in the past couple of decades in Latin America, indigenous peoples did not benefit to the same extent as the rest of the population. Poverty afflicts 43 percent of the indigenous population—more than twice the proportion of non-indigenous—while 24 percent of all indigenous people live in extreme poverty, 2.7 times more than the proportion of non-indigenous people.

This situation is also apparent in in Canada, where over 60 percent of children living on First Nations reserves live in poverty, compared with 41 percent of all indigenous children and 18 percent of all children. In the United States, it is estimated that the median income of Native American households is nearly $30,000 less than the median income of white households.

Furthermore, being born to indigenous parents substantially increases the probability of being raised in a poor household, contributing to a poverty trap that hampers the full development of indigenous children. In Ecuador, the probability of a household being poor increases by 13 percent if the household head belongs to an indigenous group, regardless of his or her level of education, gender, urban or rural location, and number of dependents. In Bolivia and Mexico, the probability is 11 percent and 9 percent higher, respectively.

Contrary to common assumption, nearly half of Latin America’s indigenous population now lives in urban areas, but often are exposed to new dimensions of exclusion. About 36 percent of all indigenous urban dwellers live in insecure, unsanitary, and polluted environments, which contribute to increased health risks. For example, in Mexico, indigenous urban dwellers have less than half the access to electricity and piped water than other city dwellers have, one-fifth the access to sanitation, and live nearly three times more often in houses with dirt floors.

World Bank data also show that while improved educational outcomes among indigenous people have been one of the most important advances in the last decade in Latin America, additional efforts are needed to increase education quality, make it culturally appropriate and bilingual, and to reduce a wide gap in education between indigenous men and women.

In cities, indigenous people work mostly in low-skill/low-paying jobs. In countries with large urban indigenous populations, such as Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Mexico, the percentage of indigenous persons occupying high-skill and stable jobs is two to three times smaller than the percentage of non-indigenous people. Indigenous workers, who often are engaged in informal occupations, are less likely to receive retirement and health insurance benefits. Household data show that, regardless of educational background, gender, age, number of dependents, and place of residence, an indigenous person likely earns 12 percent less than a non-indigenous person in urban Mexico and about 14 percent less in rural areas. In Bolivia, an indigenous person likely earns 9 percent less in urban settings and 13 percent less in rural areas. In Peru and Guatemala, indigenous persons earn about 6 percent less than non-indigenous populations. And Bolivian indigenous women earn about 60 percent less than non-indigenous women for the same type of jobs.

Another common problem in the Americas is glaring health disparities that reflect not only high poverty levels but wide health care access gaps between indigenous peoples and the rest of the population. PAHO/WHO data show that infant mortality in consistently higher among indigenous children than among non-indigenous children in 11 countries in Latin America for which data were available. In Panama and Peru, for example, infant mortality among indigenous children was three times higher than in non-indigenous children. The data also show greater maternal mortality among indigenous women and that under-5 mortality rates are far higher for children of indigenous background than for those of other ethnic groups. In a national survey study throughout Brazil, indigenous women were found to have a higher prevalence of obesity, anemia, and hypertension. In Canada, infant mortality was 4.6 times higher in Inuit-inhabited areas than that reported in non-indigenous-inhabited areas. In the United States, under-5 mortality for Native Americans at 8 deaths per 1,000 births, is second highest after African Americans at 11 deaths per 1,000 live births. From 2012–2015, compared with white women, the incidence of severe maternal morbidity was 148% higher for American Indian/Alaska Native women in the United States.

High rates of chronic undernutrition among indigenous children further undermine their human capital development. In Latin America and the Caribbean, prevalence rates of stunting in children are higher in indigenous than in non-indigenous peoples. For example, in Guatemala, where levels of stunting are high compared with other countries, 58 percent of indigenous children are stunted, compared with 34 percent of non-indigenous children.

Higher prevalence of health risk factors, chronic diseases, and mental and substance use disorders are also found among indigenous people. In the United States, CDC reports evidence that colorectal cancer screening prevalence is lowest, binge drinking is highest, motor vehicle crash rate is highest, and drug- induced death rates are highest in American Indian/Alaskan Natives compared to other ethnicities. Additionally, in the United States, smoking prevalence is highest among indigenous youth compared to non-indigenous peers. In Canada, the suicide rate for First Nations males aged 15–24 is four times higher than that of non-indigenous young people. First Nations populations are particularly at risk for substance abuse, contracting tuberculosis and/or HIV, and developing diabetes. Indigenous women in Canada are five to seven times more likely than other women to die as the result of violence.

These data provide compelling evidence that poverty among indigenous people in the Americas is about more than income. Indeed, unsafe and unsanitary living conditions and wide health and education disparities are all measures of multidimensional poverty that require broad, sustained, multisectoral efforts to overcome. To be effective, however, these efforts must be rooted in consultation with and active participation of indigenous people, while respecting their cultures and identities. As the recent experience in Ecuador shows, the voices of indigenous peoples are now an integral part of the political process. They demand to be heard and must be part of the planning and implementation of economic and social policies and programs to ensure acceptance and sustainability.