Let’s not forget about Mental Health during COVID-19!

“Thus the first thing that plague brought to our town was exile…….It was undoubtedly the feeling of exile—that sensation of a void within which never left us, the irrational longing to hark back to the past or else to speed up the march of time, and those keen shafts of memory that stung like fire.”

Albert Camus (1957 Nobel Prize Laureate for Literature), The Plague, 1947

Growing numbers of infected people, loss of life, and an economic free-fall not experienced since World War II, are some of the casualties of the COVID-19 pandemic. IMF estimates show that 170 countries will see income per capita go down, and World Bank Group projections suggest that rising unemployment and loss of income, including in some countries a significant drop in remittances, could push between 71 and 100 million people into extreme poverty.

Daily personal routines have been altered by social distancing measures adopted to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, impacting people in many different ways. The lack of interpersonal contact with loved ones and peers is contributing to feelings of isolation and loneliness; detachment from our communities is depressing us; and fear of becoming infected or of loved ones falling ill worries and makes us anxious. In large measure, a sense of being in “exile” has engulfed us as we drift through the sameness of days, feeling unmoored and uncertain about the repercussions of the pandemic.

Given the intense disruption brought by COVID-19 to our everyday life, it is of great importance to understand how the pandemic is affecting mental well-being and what can be done to help people cope and deal with its consequences in the short- and medium-terms. In answering this question, we need to learn from past crises as well as to look at the emerging evidence from the current pandemic.

The Impacts of Unemployment and Loss of Income

The layoffs and job losses brought on by lockdowns have been enormous, particularly for people with only basic levels of education and in the poorer segments of society, while telework arrangements have protected the employment of highly skilled and educated people. Across countries, ILO estimates show that full or partial lockdown measures are affecting almost 2.7 billion workers – four in five of the world’s workforce. In particular, workers in sectors such as food and accommodation (144 million workers), retail and wholesale (482 million), business services and administration (157 million), and manufacturing (463 million), which account for up to 37.5 per cent of global employment, are feeling the “sharp end” of the impact of the pandemic. COVID-19 has had disproportionate effects on women and their economic status, since women are more likely than men to work in social sectors — such as service industries, retail, tourism, and hospitality, that require face-to-face interactions, and hence, are hit hardest by social distancing and mitigation measures.

As discussed in a paper by researchers from the Urban Institute, the experience from previous global crises, such as the Great Recession of 2008, shows than being out of work for six months or more is associated with lower well-being among the unemployed, their families, and their communities. While fiscal stimulus and targeted social transfer programs can help mitigate the consequences of long-term unemployment, a decline in family income due to a worker’s lack of earnings directly reduces the quantity and quality of goods and services the worker’s family can purchase and exacerbates stress as well. The erosion in the tax base used to fund essential public services, such as essential medical care, can negatively affect individuals and families by constraining access to these services when needed.

Impact on Mental Health

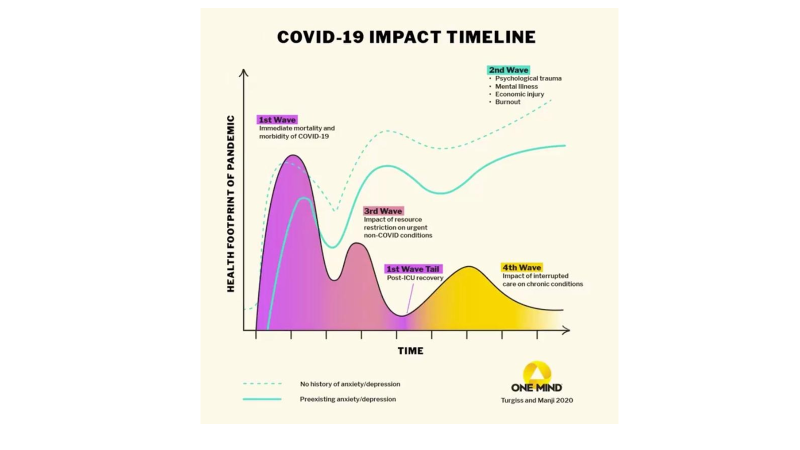

The devastating impact of COVID-19 disease on people’s physical health is well documented, with more than 22 million people infected, almost 800,000 deaths, and many that survived infection left experiencing persistent symptoms long after hospital discharge. Much less understood is the impact of high levels of stress on people resulting from the adoption of social distancing measures to contain and mitigate COVID-19 and from the economic downturn and income loss to households. The graph below depicts a COVID-19 physical and mental health impact timeline.

Fear, pervasive anxiety, frustration, and anger experienced by adults and children can be overwhelming and aggravated by social isolation and loneliness among the elderly, who are a higher risk of developing severe symptoms or die from COVID-19 disease. These negative psychological effects are associated with stressors such as long duration of quarantines, infection fears, frustration, boredom, sadness, grief, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma and discrimination. Some of the symptoms of mental health problems include changes in sleep or eating patterns; difficulty sleeping or concentrating; worsening of chronic health problems and mental health conditions; and adoption of risky behaviors such as increase in tobacco use, alcohol abuse, and substance use.

More specifically, research in countries is showing how the pandemic is impacting the general population. A health tracking poll conducted in April 2020 in the United States indicates that an increasing share of people reported worrying about economic impacts, with more than half now reporting being worried that their investments will be negatively impacted for a long time (59%) and that they will be laid off or lose their job (52%), nearly half worried they will lose income due to a workplace closure or reduced hours (45%), more than half (53%) worried that they or a family will get sick from coronavirus, and nearly six in ten adults (57%) being worried they will put themselves at risk of exposure to coronavirus because they cannot afford to stay home and miss work. More troubling, the results of the poll indicate that more than four in ten adults overall (45%) feel that worry and stress related to coronavirus have had a negative impact on their mental health, up from 32% in early March 2020. Similarly, research that examined whether intolerance of uncertainty and coping responses influence the degree of distress experienced by the U.K. general public during the COVID-19 pandemic, indicates that around 25% of participants demonstrated significantly elevated anxiety and depression, with 14.8% reaching clinical cutoff for health anxiety. Further research from China found that 35% of people experienced mental distress, such as panic disorder, anxiety, and depression, during the first month of the COVID-19 outbreak and that these levels continued as the disease spread over the following months.

How are Lockdowns Impacting Children and Young Adults?

The Great Lockdown has affected close to 1 billion children and adolescents worldwide, upending their daily routine and isolating them from their social structures. A recent study examining the psychological impact on youth from Italy and Spain, shows that 85.7% of the parents perceived changes in their children´s emotional state and behaviors during this period. The most frequent symptoms identified included difficulty concentrating (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), feelings of loneliness (31.3%), uneasiness (30.4%), and worries (30.1%). The study also reported that children of both countries used electronic devices more frequently, spent less time on physical activity, and slept more hours. Moreover, when family coexistence became more difficult, the situation was more serious, the level of stress was higher and parents tended to report more emotional problems in their children. Death of parents or other family members due to COVID-19 may also spur a great amount of grief among children that would need to be dealt with. In addition, long-term school closures may further impact negatively the well-being of school-age children as they lose access to meal programs, academic support, physical and social activities, and reduced face-to-face engagement with peers.

It has also been suggested that stressors from the pandemic, such as reduced family income, food insecurity, parental stress, and child abuse, can negatively impact children’s developing brains, immune systems, and ability to thrive. While some effects will be immediate, many will surface decades from now in the form of mental, social, and physical health problems (e.g., higher risk of metabolic syndrome and physical health problems in adulthood). A related study in China has highlighted the importance of the link between sleep, health, and family factors, even during a period in which families are confronted with dramatic lifestyle changes and grappling with heightened health concerns related to the pandemic. Disrupted and insufficient sleep has been linked to immune system dysfunction (e.g., increase in cytokines, such as interleukin), impeding resilience to infection in young children during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Isolation and lack of interaction with other people are also negatively impacting the mental health of young adults ages 18-24. Existing mental illness among adolescents may also be exacerbated by the pandemic, and with school closures, they may have limited access to mental health services. Recent data from the CDC illustrate this problem by showing that young adults in the United States are among the groups disproportionately affected by the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling with issues such as anxiety/depression (31%), trauma/stressor-related disorders (26%), starting or increasing substance use (13%), and seriously considering suicide (11%). Preliminary results of a study carried out by Uribe and team at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana focusing on mental health and resilience in young adults in Bogota, Colombia during the COVID -19 lockdown, also evidence the high mental health toll that social distancing measures are having on young adults aged 18-24 years. While 59% of males and 70% of females presented depressive symptoms, 47% of males and 56% of females had anxiety symptoms. Substance use and addiction, in particular, can have long-term impacts on young people, as they can affect brain development, occur more frequently with other risky behaviors, such as unprotected sex and dangerous driving, and contribute to the development of adult health problems, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, and sleep disorders.

The daily attachment to laptops, desktops, and the multi-functional smartphone, which have become “virtual bridges” for interacting with the outside world during the pandemic, may pose additional risks, particularly to children and adolescents. Hyper connectivity has the potential to further change patterns of social interaction, as online interaction may become a “new normal,” substituting for face-to-face interaction--essential to the give-and-take functioning of families, communities, and workplaces. Digital media consumption may also facilitate bullying, harassment, social defamation, and hate speech because potential costs of such behavior are reduced and the ease of engaging in behaviors that harm others or ourselves is increased. And, excessive digital media use can negatively influence the development of cognitive (thinking, imagining, reasoning, and remembering abilities) and behavioral (reactions or actions that we take in response to stimuli present in our environment) skills and even mental and physical health.

Impact on Frontline Health Workers

In many countries, as COVID-19 cases surged, hospitals were overwhelmed, and work demands on frontline health care workers increased significantly, particularly in facilities with lower physician-or nurse-to-patient densities. As a result, they are at increased risk of burnout and suffer from mental health issues, including depression and substance use.

Risk of Suicides

Suicide is a terminal outcome in the spectrum of mental health problems. Accumulated evidence from countries around the world indicates that global crises, that lead to severe social and economic disruptions, similar to those caused now by the COVID-19 pandemic, are associated with increases in suicide, particularly in males of working age. This occurs as the result of the negative effects of unemployment and job insecurity, as well as effects of financial loss, bankruptcy, and home repossession on individuals and households, which may lead directly or indirectly to mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and binge drinking and then to suicidal behavior.

A study that estimated what the suicide rates would have been during and one year after economic/financial crises of the 1970-2011 period in 21 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries if the suicide rates had followed the pre-crisis trends, found that all the crises led to excess suicides. Among males, the excess suicide rate (per 100 000 persons) varied from 1.1 to 9, and among females, from 0 to 2.4. In terms of actual numbers, these crises caused more than 60,000 excess suicides in OECD countries. Another study showed that after the Great Recession of 2008 in the United States, the number of suicides increased due to the negative effect of the crisis on the mental health of individuals and the decrease in their future expectations. These findings are corroborated by studies done in Ireland, that showed that five years of economic recession and austerity had a significant negative impact on rates of suicide in men and on self-harm in both sexes, and in Greece, that found a clear increase in suicides among persons of working age that resulted from the economic crisis of 2011-2013.

What to Do?

While a vaccine and new diagnostics and therapies are on the horizon, it seems that we are at the cusp of a transition from a world that we knew well at the beginning of 2020 and that in many ways has now been shattered, to a yet unknown “new normal”.

Should we despair, or use this time as a “window of opportunity” to reflect, learn from the fact that no country, not even the richest one in the world, was prepared to deal with the onslaught of the fast-spreading novel coronavirus, and perhaps start thinking on how to build better for the long term? Looking at the glass half full, we will discover that not everything is lost. As human beings we have the capacity to assess reality, learn from past experiences and accumulated knowledge, and chart a path forward.

The mental health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic is only beginning to show itself. Although we cannot predict the scale of its impact, lessons from past crises can offer guidance on how to mitigate and address this challenge.

Moving forward, it is crucial that we ensure that along with health and economic emergency response programs, social and psycho-social support interventions are included to provide required support to people in need, both those already suffering from mental disorders pre-pandemic and those newly affected. This would require the allocation of resources targeted to develop effective communication to the population and improve the quality and quantity of mental health services integrated as part of primary health care and social support service delivery platforms at the community level. It will be of critical importance that these platforms include mechanisms for surveillance, reporting, and intervention, particularly to track and address gender and domestic violence and child abuse during lockdowns, and that services delivered be organized following stepped-care approaches—the practice of delivering the most effective, least resource-heavy treatment to people in need, and then stepping up to more resource-heavy treatment based on patients’ needs. Levering information technology will facilitate the provision of online mental health and peer-to-peer support services while helping overcome stigma barriers, particularly among adolescents.

Monitoring and additional research are also needed to track and understand the long-term mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, to guide action on the basis of evidence.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that while some people may require medication and social support to deal with fear, loneliness, or grief, we need to avoid rushing to medicalize the response to “normal unpleasant emotions” such as feeling bored and confusion during lockdowns. Although these feelings may be intolerable sometimes, they “do not need medical treatment any more than everyday unhappiness requires an antidepressant”.

Image Credit: Srdjanns74, Stock Photos