Public Health Investments and Economic Gains: Learning from Latin America and Caribbean History in the Time of Coronavirus

With the advent of 2019-nCoV in China, the world has woken up once again to the inexorable reality that globalization, both the movement of people and goods and services across countries and from continent to continent, enables the spread of viruses and disease.

While the coronavirus appears to be more infectious than SARS but less lethal, it is already creating global havoc. As the number of cases increases in China, and new cases are detected and confirmed in different countries, airlines have cancelled flights to and from China, the global economy is taking a hit, and fear among the population is rising. The World Health Organization (WHO) with support of social media companies is stepping up its fight against “disinformation” and “fearmongering.” Countries are also starting to issue calls that the virus is a “serious” health threat.

All this seems like the rerun of an old movie. I remember vividly the days when working at the World Bank Group (I retired in August 2019 after 32 years of service globally), I was part of quickly assembled core task teams that were mandated to prepare in a matter of days, program and budgetary proposals that eventually became the US$1.3 billion Global Avian Influenza Preparedness and Control Framework Program in 2006 and the US$390 million Ebola Emergency Response Program for West Africa in 2014. In those days as today with coronavirus, panic and uncertainty in different forms were common currency.

The question that we need to ask as these health events are not something new, is what have countries learned to be ready to deal with these threats? Unfortunately, in many instances, it seems that once the sense of fear has diminished and the outbreak controlled, it is back to the common practice of undervaluing the importance of having in place strong “intelligence systems” in the form of disease surveillance systems, public health labs, and trained personnel, both in the veterinary and public health sectors operating in a coordinated manner. It is clear that all countries need to have in place robust early detection and confirmation of cases, as well as preparedness platforms, including medical care systems, along a continuum of action, to deal on time and effectively with disease outbreaks. Perhaps the most common “fatality” post-disease outbreaks is the lack of predictable and sustained funding for disease surveillance and emergency preparedness in national budgets that are protected from budgetary cuts that follow short-term “fiscal rectitude” arguments or changing investment priorities that are assumed to have a higher-rate of return.

Some Historical Antecedents

If we look back in history, there are plenty of examples that illustrate that this should not be the case. History shows that travelers have spread contagious diseases for centuries. At the same time, the threat of disease has been a driver for supporting the continuous development of global public health practices and institutions, building upon accumulated and new scientific knowledge and technological know-how. The history of public health in Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, is replete with efforts in sanitation, hygiene, and disease control, especially directed at old scourges such as yellow fever and malaria.

Since colonial times, outbreaks of disease were common in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, largely as a result of maritime trade and export of agricultural products and minerals that helped integrate them into the world economy, as well as the development of indigenous commercial interests. In 1515, a smallpox epidemic in Hispaniola—now the Dominican Republic and Haiti—spread to neighboring islands and to the mainland, leaving a toll of thousands of victims. This episode was to be registered as the first epidemic in the colonial period. In the sixteenth and following centuries, epidemics of different kinds made devastating sweeps across the Americas.

As the spread of disease largely reflected the maritime basis for trade among the colonies, and between the colonies and the metropolitan powers, such as Spain and Portugal, the principles of isolation and confinement followed in Europe to control disease outbreaks, were also applied in Latin America and the Caribbean. In practice, beginning in Hispaniola in 1519, in accordance with the 1423 Venetian quarantine control system, measures to cope with epidemics centered on the detention of ships and the isolation of their crews and passengers outside the harbors until sufficient time had elapsed without the outbreak of “pestilences.”

The latter years of the 19th Century and the early 20th Century saw various attempts by the Latin American and Caribbean countries and the United States to adopt uniform quarantine regulations at different international conferences, under the aegis of the newly established Pan American Sanitary Bureau in 1902, that preceded the establishment of WHO. These sought to remove barriers to steam navigation, and to codify new preventive measures into specific health legislation and programs based on the great microbiological discoveries of Pasteur, Koch, and Klebs that had revolutionized public health practice in Europe.

From 1880 to 1930, national health departments, the forerunners of the present-day ministries of health, were created within the ministries of the interior in most Latin America countries. The initial mission of these departments was to combat the infectious diseases that hampered maritime trade in major port cities and diminished labor productivity in the countries' export-oriented economies, resting on the acceptance and application of the germ theory in disease causation that was supported by leading Latin American scientists such as the Brazilians Oswaldo Cruz and Carlos Chagas, the Cuban Carlos J. Finlay, as well as Walter Reed and others in the United States. As a result of these efforts, great inroads were made in the conquest of many of the diseases that had warranted quarantine, particularly yellow fever, commonly known as “Yellow Jack”. This represented the principal scourge of international trade throughout the colonial period, up to the beginning of the 20th Century. As a result of these efforts, yellow fever disappeared from its well-established foci, Havana, Panama, and Guayaquil.

The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 was only possible because of the success of major public health efforts against yellow fever and malaria, diseases that took a heavy toll in terms of lives lost among construction workers. In turn, the activities undertaken to help build the canal added further impetus to the development of sanitation programs in the countries of the region by supporting research on the etiology and transmission of yellow fever and malaria which led to the design of more effective control measures.

In subsequent periods, the activities of the national health departments expanded with the support of the International Health Commission of the Rockefeller Foundation to undertake land sanitation programs centered on the control of hookworm infection and malaria, with the aim of improving the productivity of workers in exporting regions, such as those growing bananas and coffee. The support of the Rockefeller Foundation was also important for the establishment in 1918 of the School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, following the example of the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore that was founded in 1916 also with a grant from the Foundation. Additionally, the Foundation provided fellowships for the training of Latin American public health cadres (for example, epidemiologists, biostatisticians) to staff the departments, manage public health programs, and conduct public health research.

During the 1930s and 1940s, changing economic and socio-political conditions led to the elevation of the health departments to the ministry level and the concurrent expansion of their activities to include the provision of personal health services for the unemployed and indigent populations. Similarly, the development of medical care programs under social insurance schemes was directly linked to the process of industrialization. In satisfying the demands of organized labor forces, these programs served as an important mechanism of social stabilization. In the last three decades of the 20th Century and in the early 21st Century, the most important public health achievements in the Latin American and the Caribbean region have continued to be in the areas of infectious disease control. Mortality rates have declined in virtually every country of the Americas, mainly at the expense of important declines in infectious diseases.

Take-Away Message

As we have seen throughout history, infectious diseases have recurrent patterns of outbreak and control or silent occurrence due to ecologic variables that are often difficult to manage, mainly because of social, political, and economic limitations on the application of known, effective measures for controlling their spread and treating infected people. The recent outbreaks of infectious disease in the world clearly signal the need, as we saw from the historical examples in Latin America and the Caribbean, of building and maintaining strong institutions and systems to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and protect public health and the social and economic well-being of countries in an ever more interconnected world. And this risk stands to be more menacing in the face of inaction and misplaced social and economic priorities when one adds the risks posed by rapid urbanization and the conglomeration of people living in large mega-cities with limited access to basic services, climate change that is driving the emergence of new pathogens such as the coronavirus and the reemergence of known pathogens such as Ebola, social conflict and wars that not only breed social dislocation and the displacement of large numbers of people, but also that hinder public health action, and massive disruption of global supply chains in interconnected economies.

Indeed, commitment to public health objectives and program needs to be firmly entrenched in the development programs of governments and supported with the necessary budgetary allocations in a sustainable way. Financing essential public health functions is a government responsibility as it a basic public good. In most of the world, however, misplaced priorities translate into very low budgetary allocations for essential public health functions, sometimes amounting to less than 1% of the total public expenditure on health.

While donor contributions help, particularly in low-income countries, governments can mobilize additional tax revenue as a share of GDP to fund and sustain public health and essential medical care services via better tax administration (including value-added taxes), tackling tax avoidance and evasion (e.g., taxing financial capital flows), broadening the tax base by removing cost-ineffective tax expenditures (e.g., fuel subsidies), and increasing excise taxes on unhealthy products (including on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened drinks). This is needed, as clearly articulated in a recent article in Foreign Affairs by Nobel Laurate in Economics, Joseph E. Stiglitz and two of his colleagues, because

“The state requires something simple to perform its multiple roles: revenue. It takes money to build roads and ports, to provide education for the young and health care for the sick, to finance the basic research that is the wellspring of all progress, and to staff the bureaucracies that keep societies and economies in motion. No successful market can survive without the underpinnings of a strong, functioning state.”

So, it would be critical that institutions such as the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund spearhead efforts to include robust, well structured and funded public health platforms, including disease surveillance and preparedness, as a critical indicator in country credit and investment risk assessments ratings, which are used to determine financing terms and conditions of officially supported export credits, as well as for commercial loans and direct investment decisions by financial and corporate sectors. This type of institutional “nudge” at the international level is needed to prevent governments, along with other global stakeholders, from forgetting the lessons of recent disease outbreaks, with their associated high human toll and significant economic losses.

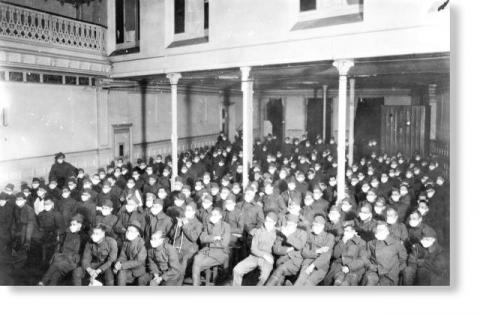

The PHOTOGRAPH taken in 1918 at the US Army Hospital Number 30 in Royat, France, is from the Prints and Photographs Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine. It was included in Fee E et al article (2001). The pictures shows servicemen watching a movie during the Influenza Pandemic spread worldwide through 1918–1919. The article notes that “while a civilian debate raged over the compulsory wearing of masks as a means of slowing the transmission of influenza, military authorities through the chain of command were more readily able to impose this requirement on the troops.” (Fee, Brown, Lazarus, Theerman, 2001).

The second photo is from https://www.dominicavibes.dm/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/pp-zika-mosquitos-getty.jpg