Retracing Darwin’s Footsteps in the Galapagos

In the latter part of February 1535, a caravel carrying Fray Tomas de Berlanga, bishop of Panama, enroute to Peru, drifted off course in the Pacific Ocean amid the equatorial doldrums, disappearing wind, and strong currents to an unknown and strange land. In his report to Charles V, King of Spain, who had mandated him to journey to settle disputes in his new empire, he described the nature of the shore in vivid detail:

“There were some small stones that we stepped on as we landed, and they were diamond-like stones, and others amber colored; but on the whole island I do not think that there is a place where one might sow a bushel of corn, because most of it is full of very big stones, so much so that it seems as though at some time God had showered stones; and the earth that there is, is like slag, worthless, because it does not have the virtue to create a little grass, but only some thistles, the leaf of which I said we picked.”

Three centuries later, Charles Darwin, sailing in the H.M.S. Beagle, arrived in the Galapagos Islands, an archipelago located six hundred miles westward of the coast of Ecuador, as part of his five-year voyage to South America and the South Pacific. Upon landing on Chatham Island (now San Cristobal), Darwin noted in similar terms that:

“Nothing could be less inviting that the first appearance. A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is covered by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life.”

As I found out on a recent visit to eight islands in the Galapagos aboard the Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic’s Endeavor II vessel, the observations made by de Berlanga and Darwin have in large measure withstood the passage of centuries. Indeed, one is not only captivated by a sense of distance and isolation from mainland Ecuador, but is confronted by a strange mixture of volcanic terrain pummeled by strong ocean currents, tick mists that make the islands disappear and then reappear at sunrise, leafless shrubs, large cacti, and strange animals, that are not afraid of humans.

While one finds scarce remains of visits by pirates, buccaneers, and whalers from the late 1500s through the early 1800s, and later of repeated, but failed, colonization attempts by penal colonies and settlers, the archipelago continues to be, as observed by Darwin during his visit in 1835, “a little world within itself, or rather a satellite attached to America, whence it has derived a few stray colonists, and has received the general character of its indigenous productions.”

The geological formations in the islands combine rocky stretches of shoreline, pristine beaches with sand of various colors (rust red as in Rábida, created from lava with high iron oxide; ash black in Togus Cove; and beautiful white in Cerro Brujo or Wizard Hill), and active volcanos such as the Salcedo Volcano in Isabela Island and Fernandina Island, at about 1 million years old, the youngest and most volcanic of the archipelago as well as long-extinguished ones such as Ecuador Volcano, bisected by the Equator line on Isabela Island, that has collapsed and slumped away into the Pacific Ocean. There are also verdant highland regions as in Santiago Island and patches of red Sesuvium, a plant that adds color to the uninhabited areas of San Cristobal. Beautiful isolated rock outcroppings such as the León Dormido (“Sleeping Lion”), facing San Cristobal Island, offer a dreamlike view at sunset. And “in vivo” geological forces, such as the marine reef off the coast of Urbina Bay that was uplifted by as much as 15 feet, are a testament to unrelentless volcanic forces, oceanic currents, and trade winds that shape the islands.

The unique fauna of the Galapagos Islands, which transports us to another era in time, stimulated “the origin” of Darwin’s ideas about evolution. Indeed, an observation recorded in The Voyage of the Beagle, a journal that underpinned his seminal work On the Origin of the Species, changed the scientific understanding of the natural world by putting forward his theory of “descent with modification” by noting:

“Considering the small size of the islands, we feel the more astonished at the number of their aboriginal beings, and at their confined range. Seeing every height crowned with its crater, and the boundaries of most of the lava-streams still distinct, we are led to believe that within a period geologically recent the unbroken ocean was here spread out. Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact--the mystery of mysteries--the first appearance of new beings on this earth.”

The richness of the species that inhabit the Galapagos Islands, “peculiar to the group” and some “found nowhere else”, include the blue- and red-footed boobies, frigate birds, and several species of finches in different islands. Other species, like the American flamingo and land iguanas, have a more restricted distribution, and some species are restricted to just one island, such as the waved albatross, that nests exclusively on Isla Española, and the flightless cormorant, found only on Isabela and Fernandina Islands. The “saddle-shaped” giant tortoises, iconic species of the archipelago, with an average life expectancy of close to 200 years, move between the highlands and dry zones, depending on the island and season.

The wildlife at sea include cold-water penguins, green sea turtles, marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, and Sally Lightfoot crabs, along with many species of sea and shore birds. There is also a rich and diverse underwater world, nurtured by diverse ocean currents that converge on these remote shores, including tropical-reef fish, whales and dolphins, and a variety of shark species, including white-tip, Galapagos, and hammerhead sharks.

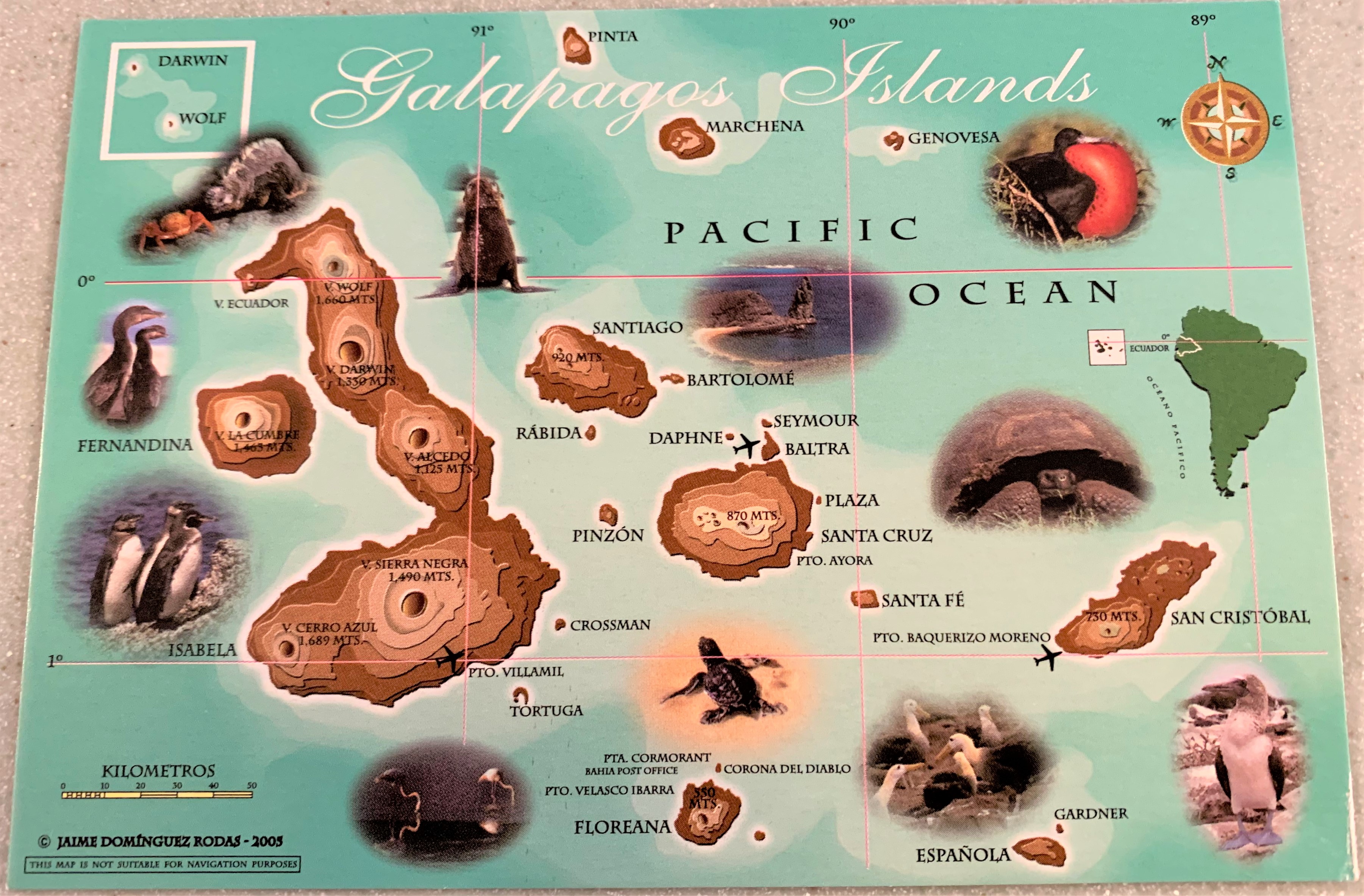

About 30,000 people live in four of the 13 large islands in the archipelago, making a living from tourism, fishing, and farming. While Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, on San Cristobal Island, is the capital of the Ecuadorian Province of Galapagos, over half of all Galapagueños live in the city of Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island, which is the center of tourism and conservation.

As an Ecuadorian living abroad for most of my adult life, I felt great pride for the work done by my compatriots in preserving this UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site. After officially taking possession of the Galapagos Islands in 1830, the Ecuadorian Government converted in 1959 all parts of the islands that were not inhabited by humans as a National Park (96% of the total archipelago surface area). The same year, the Charles Darwin Foundation was established with the objective of conserving the unique Galapagos ecosystems, and the Charles Darwin Research Station was inaugurated in 1964 to conduct scientific studies aimed at protecting indigenous plant and animal life. In 1968, the Galapagos National Park Service, a governmental institution, was created to protect the archipelago.

I also felt great pride observing that the high-quality service standards aboard the Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic Endeavour II vessel, depends for its operation on a top-quality Ecuadorian crew and a superb team of knowledgeable and diplomatic technical guides and staff, many of them Galapagueños, to offer to visitors an environmental, historical, cultural, and culinary exploration at its best.

Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick, observed in 1854 about the Galapagos Islands that “the special curse, as one may call of the Encantadas*, that which exalts them in desolation...is that to them change never comes-neither the change of seasons or of sorrows”. Echoing those words, I concluded my visit with a deep conviction that we all have an obligation to protect the Galapagos Islands as a legacy of humanity for the enjoyment of future generations. This realization acquires more relevance in periods of fiscal austerity as the one currently facing the Government of Ecuador, when “siren calls”, both domestic and international, try to use cyclical downturns as an opportunity to advance short-term, self-serving economic interests, without due consideration to the long-term impact on the environment.

I also feel that globally we have an obligation to help mobilize additional financial resources, to complement regular budgetary allocations by the Ecuadorian Government, to support with adequate funding levels the critical conservation work of the Galapagos National Park Service and the Charles Darwin Foundation.

For my part, I began to do so before departing, with a contribution to the Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic (LEX-NG) Fund, that supports in the National Geographic’s Early Career Grant program and partner institutions such as the Galapagos National Park and the Charles Darwin Research Station. We should all join the good fight of protecting the unique Galapagos ecosystems, as I am planning to continue to do so. Indeed, I feel that we need to do so as the Galapagos Islands are a global public good.

Note*: Early Spanish sailors called the islands “Las Encantadas,” meaning “the enchanted,” a reference to the fact that the islands would seem to disappear and then reappear due to mists and ocean currents.