On International Day of Persons with Disabilities 2021: Let’s Remember Mental Conditions, the Oft-forgotten Disabilities

On December 3, we celebrate the International Day of Persons with Disabilities 2021. This is the day for championing the rights of persons with disabilities and to increase awareness of the challenges individuals face globally. In doing so, we need to keep in mind two-interrelated goals that require priority attention and action at the country and international levels: first, to promote the full and equal participation of persons with disabilities, including those with mental conditions; and second, to ensure the inclusion of persons with disabilities in all aspects of society and development.

Understanding Disability

Disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. Impairments refer to specific decrements in body functions and structures--often symptoms or signs of health conditions, including visual impairment (far-sightedness and near-sightedness); hearing impairment (hearing loss affecting one or both of ears); intellectual disability (significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills); and physical disability (physical impairment or reduced mobility). Activity limitations refer to difficulties in executing activities – for example, walking or eating. Participation restrictions refer to problems with involvement in any area of life – for example, facing discrimination in employment or transportation.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) advanced the understanding and measurement of disability by emphasizing the environmental factors that create disability. Disability arises from the interaction of health conditions (diseases, injuries, and disorders) with contextual factors, both environmental (e.g., products and technology; the natural and built environment; support and relationships; attitudes; and services, systems, and policies) and personal (e.g., a person’s capacities to perform actions and the actual performance of those actions in real life).

The ICF covers all human functioning and treats disability as a continuum rather than categorizing people with disabilities as a separate group: disability is a matter of more or less, not yes or no.

Global Burden of Disabilities

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, there are more than 1 billion disabled people in the world (about 15 percent of the world’s population), 20 percent of whom live with great functional difficulties in their day-to-day lives, and some experiencing multiple disabilities. Recent UNICEF figures indicate that there are nearly 240 million children with disabilities around the world. The number of people with disabilities is increasing because reductions in mortality mean that people are living longer and because an epidemiological shift in disease burden is occurring, from communicable to non-communicable diseases in a globally aging population.

Mental Disorders are an “Invisible” Disability

The concept of invisible disability refers to forms of disability that are not apparent but that impact the quality of life. Mental and substance use disorders are a widespread but often “invisible” disabilities. These conditions affect mood, cognition, motivation, and all aspects of life, including employment, relationships, housing, and personal care, and they represent a growing burden of disease worldwide.

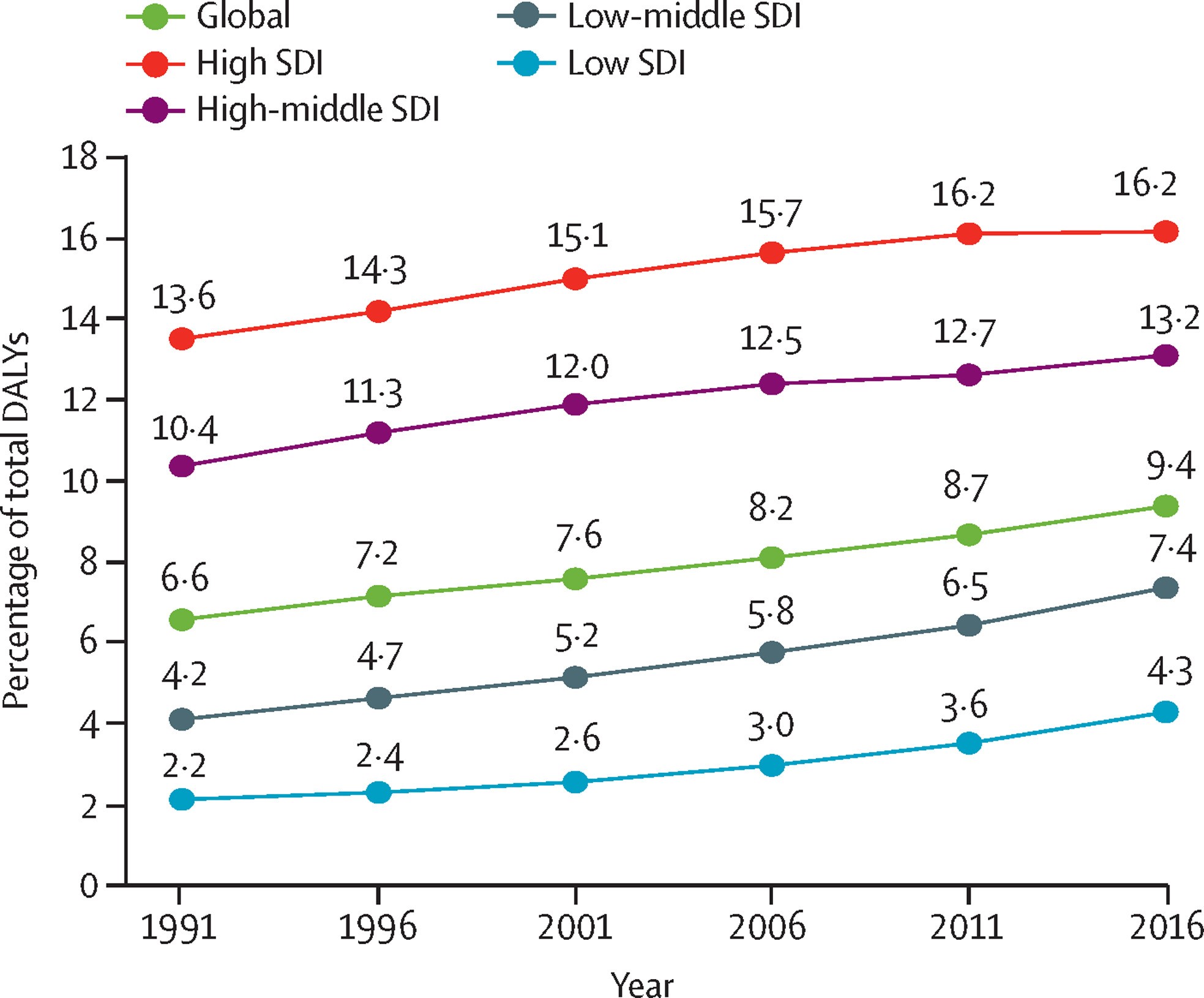

As shown in Figure 1 below, the global burden of disease attributable to mental disorders (primarily through years lived with disability and led by depressive and alcohol use disorders) has increased steadily since the 1990s. Mental disorders are among the leading causes of the global health-related burden. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 showed that the two most disabling mental disorders were depressive and anxiety disorders, both ranked among the top 25 leading causes of burden worldwide in 2019. After adjustment for the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the estimated prevalence of major depressive disorder was 3152·9 cases (2722·5–3654·5) per 100 000 population, equivalent to 246 million (212–285) people, and the global prevalence of anxiety disorders was 4802·4 (4108·2–5588·6), equivalent to 374 million (320–436) people. This burden was high across the entire lifespan, for both sexes, and across many locations. Increases in the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders during 2020 were both associated with increasing SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and decreasing human mobility.

Suicide, which is frequently caused by mental disorders, exacts an enormous toll on society. Almost one million people die each year due to suicide, which is the fourth leading cause of death among 15–19-year-olds. In some countries, suicide has overtaken complications from pregnancy and childbirth as the leading cause of death among women aged 15 to 49. For every suicide there are many more people who attempt suicide.

Dementia is another major cause of disability and dependency among older people globally. Currently more than 55 million people are estimated to live with dementia worldwide, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia and may contribute to 60-70 percent of cases.

Mental disorders are a major risk factor for developing alcohol dependency. Globally, 107 million people or 1.8 percent of the total population are estimated to have an alcohol use disorder. The results of a study on mental health and alcohol use in developing countries showed that the consumption of alcohol is heavily gendered and is characterized by a high proportion of hazardous drinking among men. Hazardous drinkers not only consume large amounts of alcohol, but also do so in high-risk patterns, such as drinking alone and binging, which are associated with depressive and anxiety disorders as well as suicide and domestic violence. In terms of drug use, it is estimated that globally around 71 million people had a drug use disorder in 2017. Most of these have an addiction to opioids, which accounts for around 55 percent of drug use disorders globally. As documented in a previous post, people are more likely to drink or use drugs as a coping mechanism "during times of uncertainty and duress," such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the face of rising unemployment and loss of income.

Data from WHO show that around half of all mental disorders start by age 14; more than 1 in 5 people living in settings affected by conflict have a mental illness; and people with severe mental disorders die 10-20 years earlier than the general population. Sadly, due to widespread global inaction, there is still limited or no access to integrated mental health services in most countries, which leaves mental health services under-resourced and creates a major problem for accessing appropriate care. Stigma and discrimination only compound the problem.

Figure 1: The rising burden of mental and substance use disorders, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, and suicide (self-harm) by socio-demographic index (SDI) groups

Source: Adopted from: Patel, V. et al. (2018), “The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development”, Lancet (London, England), Vol. 392/10157, pp. 1553-1598, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X. Data are Global Burden of Disease health data. SDI is a summary measure of a geography’s sociodemographic development and is based on average income per person, educational attainment, and total fertility rate. SDI=sociodemographic index. DALY=disability-adjusted life-year.

The Economic Impact of Mental Disorders

A growing body of evidence shows that the social and economic losses related to unattended mental conditions, including substance use disorders, are staggering.

The economic costs of mental ill health begin before individuals enter the workforce, as mental health problems typically have their onset in childhood or adolescence, accounting for the most significant disease burden among children and young people. However, often there is not appropriate care and treatment at this life stage, or it does not occur right away. This can have a lasting impact, as children and young people with mental ill health are more likely to stop full-time education early and have poorer educational outcomes.

If countries want to improve their relative ranking in the World Bank Group’s Human Capital Index, they must start investing seriously in integrated programs to promote mental well-being and prevent and treat mental ill health in communities, maternal and child health and nutrition programs, in schools, in their health systems, in prisons, and in the workplace. Investing in mental health promotion is also value-for-money, as it is much more effective to take action while people are still in school or the workplace than wait until they have dropped out of schools or from the labor market or fall into a revolving door of homelessness and incarceration.

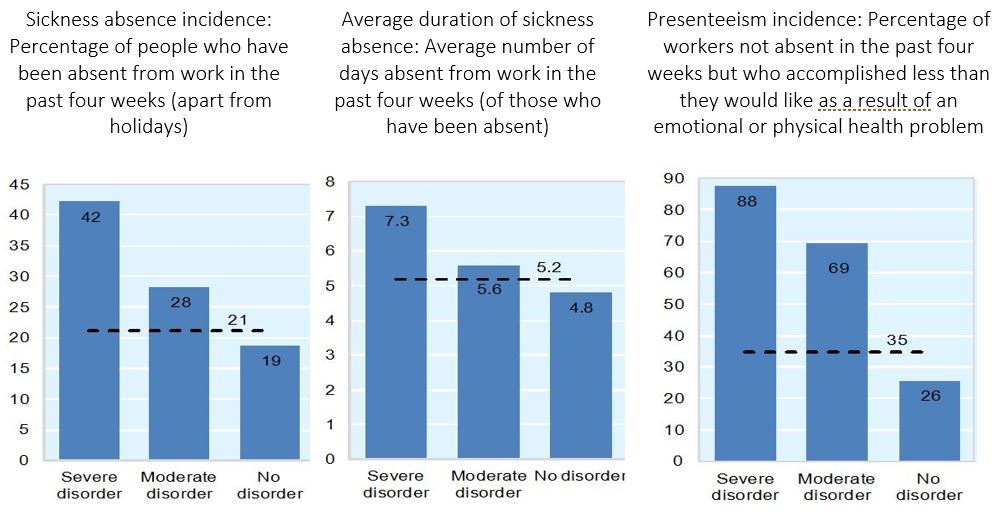

In the world’s most advanced economies – the 36 OECD countries – mental ill health affects an estimated 20 percent of the working-age population at any time, and its direct and indirect economic costs are estimated to account for more than 4.2 percent of GDP in OECD countries. In the wealthy OECD countries, which spend on average 9 percent of GDP on health care, the high economic cost associated with mental conditions is largely driven not by mental health care expenditure, but by lost productivity in the working-age population (Figure 2). Indeed, people suffering from mental ill health are less productive at work, are more likely to be out sick from work, and when they are out sick are more likely to be absent for a longer period. Around 30 to 40 percent of all sickness and disability caseloads in OECD countries are related to mental health problems, according to a 2015 OECD report.

Figure 2: Measures of productivity loss: Sickness absence incidence and duration and proportion of workers accomplishing less than they would like because of a health problem, 2010

Source: OECD (2012), Sick on the Job? Myths and Realities about Mental Health and Work.

While most people with a mental illness do work, people living with mild-to-moderate mental disorders, such as anxiety or depression, are twice as likely to become unemployed. Premature mortality is another tragic driver of lost human potential and productivity; in the typical OECD country, people with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, for example, have a mortality rate 4 to 6 times higher than that of the general population.

Takeaways

This year’s observance of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities offers a good opportunity to shine a light on some of the myths surrounding mental and substance use disorders, particularly at the workplace where we tend to spend most of our waking hours.

As discussed above, we need to be clear and accept the reality that ill mental health is not limited to persons with severe mental disorders confined to psychiatric hospitals: ill mental health is a widespread but often “invisible” phenomenon. Many of us or our parents, partners, sons, and daughters have at times felt a sense of loss or detachment from families, friends, and regular routines. We also have experienced nervousness and anxiety about changes in our personal and professional lives, as well as real or imagined fears and worries that have distracted, confused, and agitated us. While these episodes tend to be transitory for most of us, some of these conditions force us to take frequent breaks from our work, or we need time off or a leave of absence because we are stressed and depressed, or because the medication that we are taking to alleviate a disorder makes it difficult to get up early in the morning or concentrate at work. And on occasion, because of these disorders, some fall into alcoholism and drug use, further aggravating “fear attacks” or sense of alienation from loved ones and daily routines.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also negatively impacted the mental wellbeing of people. Specifically, social restrictions, unemployment, financial instability, and school closures are among the several COVID-19-related factors that have contributed to worsened mental health outcomes. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of integrated mental and physical health care, as all signs point to both possible lasting psychological impacts for COVID-19 patients, especially those who experienced long hospitalizations or those living with ‘long COVID’, as well as increased risks of contracting COVID-19 and experiencing complications for individuals living with severe mental illnesses.

To advance the disability-inclusive development agenda, therefore, we need to pay attention to common mental disorders of children and adolescents, workers, the unemployed, and their families, and not only on the provision of services for people with a severe mental disorder. Since mental disorders have multifaceted underlying factors, the path to improvement requires an integrated approach, moving away from siloed-thinking and developing strong coordination and integration of policies and services across all sectors.

A sustained commitment and effort on this front, that should not only be directed towards countries striving to improve population health, but also within organizations, including the World Bank Group, seeking to promote the health of their staff, will help honor our common responsibility to become more compassionate and understanding of the daily challenges faced by people with disabilities, and to promote the rights and well-being of persons with disabilities in our communities.