Common Myths Against Tobacco Taxation: Not Borne Out by Global Evidence

The newly-released Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General of the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020) reaffirms, on the basis of accumulated scientific evidence over the past half century, that tobacco use leads to many adverse health effects, including negative reproductive health outcomes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the risk of twelve cancers, including cancers of the lung; larynx; oral cavity and pharynx; esophagus; pancreas; bladder; stomach; colon and rectum; liver; cervix; kidney; and acute myeloid leukemia. The report is also clear in indicating that smoking cessation can be increased by raising the price of cigarettes.

It is frequent, however, to come across common claims put forward by interest groups that oppose the enactment of tobacco tax policies. These claims are often accepted uncritically by policy makers in countries at different income levels, without due consideration of available evidence. The question that we need to ask, then, is how do these claims stand vis-à-vis accumulated global evidence? Are these claims part and parcel of the “economics of deception and manipulation” that drive aggressive industry-sponsored campaigns in the pursuit of profits and market share expansion? Have the claims become just myths not borne out by accumulated country evidence?

The results of recent research done by World Bank Group teams across the world, along with additional data and information, are presented below to shed light on these questions.

Myth 1: Raising tobacco taxes undermines the tax base and lowers tobacco tax revenue.

Evidence: A report from the International Monetary Fund (Petit and Nagy, 2016) is clear in indicating that “in many countries, raising tobacco taxes can offer a “win–win”: higher revenue and positive health outcomes.” Higher tobacco taxes help boost cigarette prices, which are highly effective in reducing demand, which reduce use and the health risks associated with smoking. The positive impacts of higher tobacco taxes and prices go beyond direct health gains and indirect benefits such as reduced health care expenditures and higher productivity. Increasing tobacco taxes can also enlarge a country’s tax base to augment domestic resource mobilization to fund priority investments and programs, including the expansion of universal health coverage.

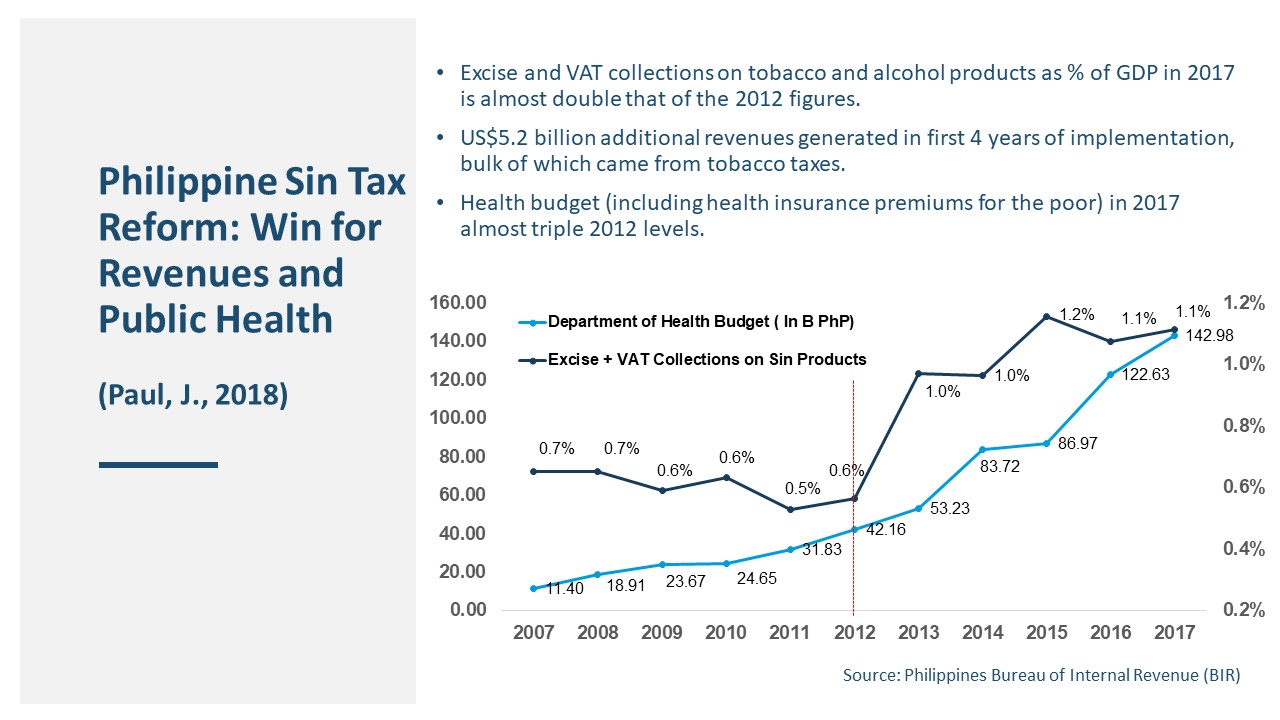

The experience of the Philippines since the adoption of the Sin Tax Law of 2012 is one of the most compelling examples of ambitious national tobacco tax reform, including reduction in the number of tax tiers, indexation of tax rates to inflation, and substantial tax increases. As shown in Figure 1, excise tax revenue on tobacco and alcohol products has more than doubled since 2012, reaching US$5.2 billion in additional revenues during the first 4 years of the Sin Tax Law implementation (about 1 percent of GDP). Tobacco accounts for about 80 percent of these additional tax revenues, which largely are earmarked under the budget to subsidize health insurance for low-income populations (Kaiser, Bredenkamp and Iglesias, 2016).

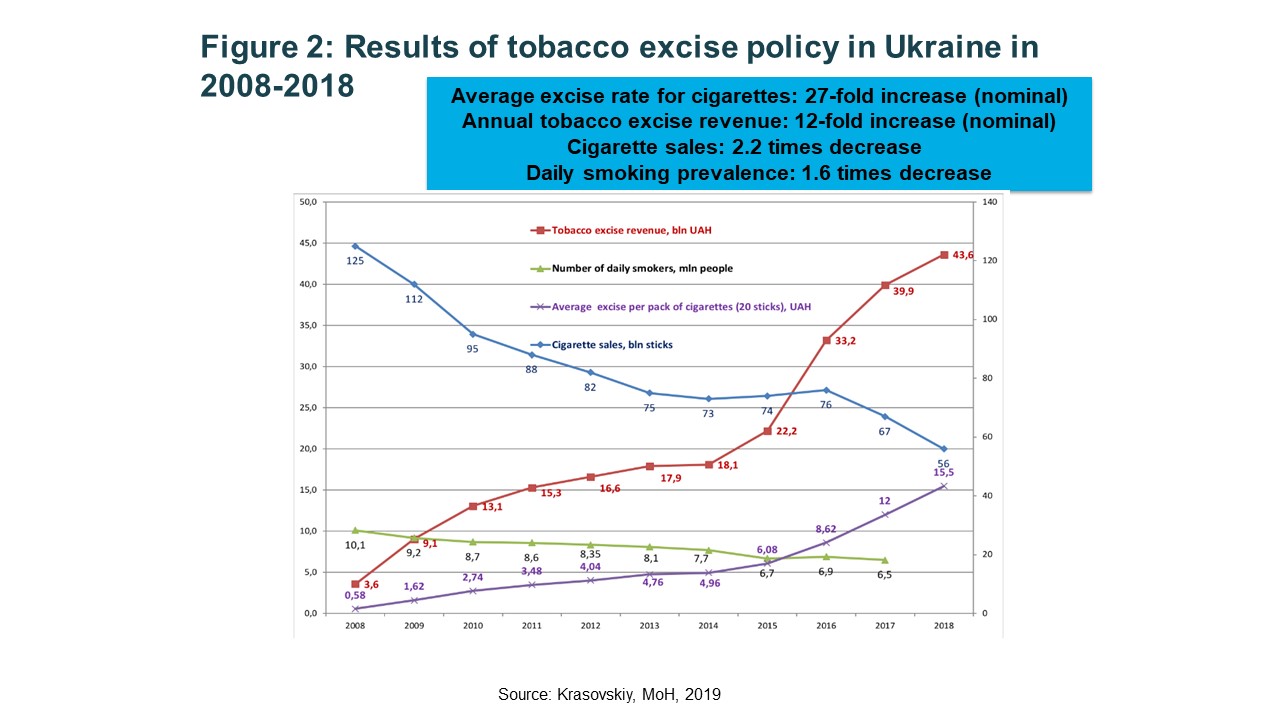

The experience of Ukraine is also noteworthy (Smits et al 2017). The total tax burden (including excise taxes, value-added tax [VAT], and other duties on tobacco as a percentage of retail price) increased from 62 percent in 2015 to 77 percent in 2019. As a result, national tobacco excise revenue increased from 22 billion UAH in 2015 (1.12% of GDP) to 40 billion UAH in 2018 (1.34% of GDP) (see Figure 2).

Moldova has also been able to collect additional tax revenue since 2017 from hiking tobacco taxes (Marquez et al, 2018). Cigarette excise tax revenue in the country increased from MDL 1.73 billion (US$ 87 million) in 2016 to MDL 2.05 billion (US$ 110.6 million) in 2017, or about 1.16 percent of Moldova’s GDP. The tobacco tax increases adopted by Moldova’s Parliament for 2018-2020 are projected to further increase excise tax revenue, hitting 3.31 billion MDL (US$194 million) or 1.45 percent of GDP in 2020.

Colombia is another example (James et al, 2017). As part of a broad fiscal reform package approved by Colombia’s Congress on December 23, 2016, the specific excise tax on a pack of 20 cigarettes was increased from COP 700 (US$ 0.25) in 2016 to COP 1,400 (US$ 0.50) in 2017, and COP 2,100 (US$ 0.75) in 2018, with annual adjustments of Consumer Price Index (CPI) + 4 points in subsequent years. The ad valorem excise tax component was maintained at 10 percent of the total sale price of a 20-cigarette pack, and the general VAT rate was raised from 16 percent to 19 percent. As a result, the total tax burden (as percentage of retail price of a pack of 20 cigarettes) increased from 50 percent in 2016 to 68 percent in 2018. The average price of a pack of 20 cigarettes increased by 42.5 percent over 2017-2018. The expected fiscal and health impacts of this measure are noteworthy. It is estimated that COP 1 trillion (about US$ 347 million) in additional revenue will be generated through 2022.

The experience of Australia, United States, and the United Kingdom (UK) provide additional evidence (Fuchs, Marquez, Dutta, Gonzalez Icaza, 2019). The annual increases in tobacco excise taxes in the past decade have led Australia to have one of the highest prices of cigarettes in the world--a 20-pack of Marlboro costs approximately US$19, while the same pack costs only US$12 in the UK, US$7 in the United States, and US$3.88 in South Africa. The high tobacco tax level has also contributed massive yearly tax revenue to the Government. In the United States, the federal cigarette tax for cigarettes was increased significantly in 2009 from US$0.39 per pack to approximately US$1.01 per pack. The tax increase was designed to help pay for the cost of children's health insurance under the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Revenues more than doubled from US$7.6 billion in 2008 to US$17.1 billion in 2010, once the law fully took effect. Although revenues have declined from the high level reached in 2010, they are still projected to represent in 2024 double the amount collected prior to the 2009 tax hike. In the UK, as a result of high taxes and prices, smoking rates have continued to decline over the past decade, and tobacco taxes contributed an estimated £10 billion in tax revenue to the UK Government over 2016-2017.

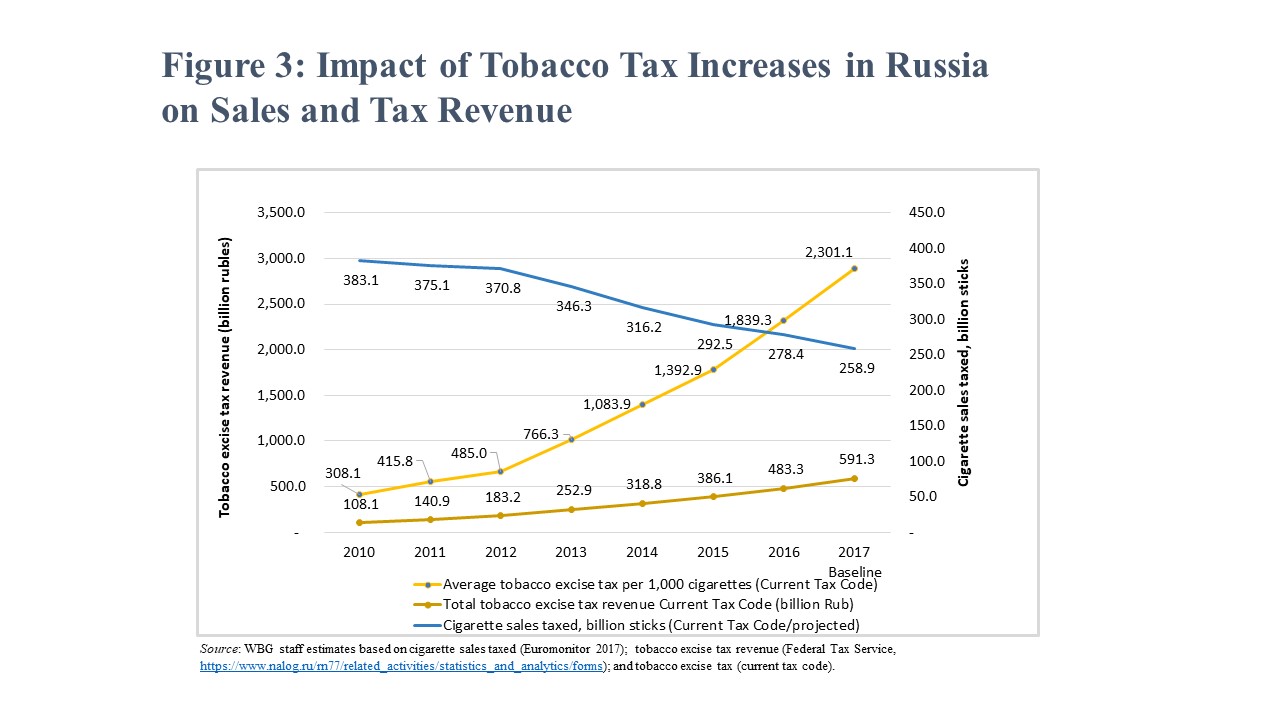

Assessment done by the World Bank Group in Russia show that that life expectancy in the country for men increased to 65.4 years in 2016, up from 58 years in 2003, and among women, to 76.2 years in 2016, up from 72 years in 2003 (Marquez and Gonima, 2018). A big contributor to this change has been the effective measures adopted to control the consumption of tobacco and alcohol over this period, including the enactment of a law on tobacco control in 2013 and regular increases in tobacco excise taxes since 2010. Because of tax and price increases, along with other tobacco control interventions, tobacco sales fell by almost 30 percent over this decade. Not surprisingly, the number of smokers also decreased, by 21 percent between 2009 and 2016, while higher tobacco taxes increased tax revenue for the country (Figure 3).

Similar experiences have been observed in other countries as varied as Botswana, China, European Union-Member States, Republic of Korea, South Africa, Turkey, and Uruguay (Marquez and Moreno-Dodson, 2017; Zheng, Hu, Marquez, Wang, Xiaoxia, 2017; Bouw, 2017; Eun Choi and Marquez, 2018; Cetinkaya and Marquez, 2017; Marquez, 2017).

Myth 2: Increased price of tobacco products due to higher taxes is regressive because the poor are affected the most.

Evidence: Country-specific research conducted by the World Bank Group, as well as the work done in the United States, show that the poor tend to smoke more and are more price responsive on average than richer individuals, so they get a far greater share of health benefits from higher tobacco taxes than they pay.

By discouraging consumption, taxes on tobacco products reduce the adverse health effects of tobacco, as well as the large associated medical and human capital costs to households and societies. Medical treatment of the numerous chronic diseases caused or exacerbated by tobacco drives up annual health care costs in public health care systems and households. Smoking reduces household earning potential and labor productivity, negatively affecting human capital accumulation and development. Hence, reducing tobacco use translates to lower smoking-related medical expenses, increases in life expectancy at birth, and reductions in disability.

A World Bank Group assessment done for Armenia (Postolovska et al, 2017) shows that increased excise taxes on tobacco would bring large health and financial benefits to Armenian households and be pro-poor: about 88,000 premature deaths, US$ 63 million of out-of-pocked medical expenditures, 22,000 poverty cases, and 33,000 cases of catastrophic health expenditures would be averted. Government savings on tobacco-related treatment costs would amount to US$26 million. Half of the premature deaths and 27 percent of poverty cases averted would be concentrated among the bottom 40 percent of the population.

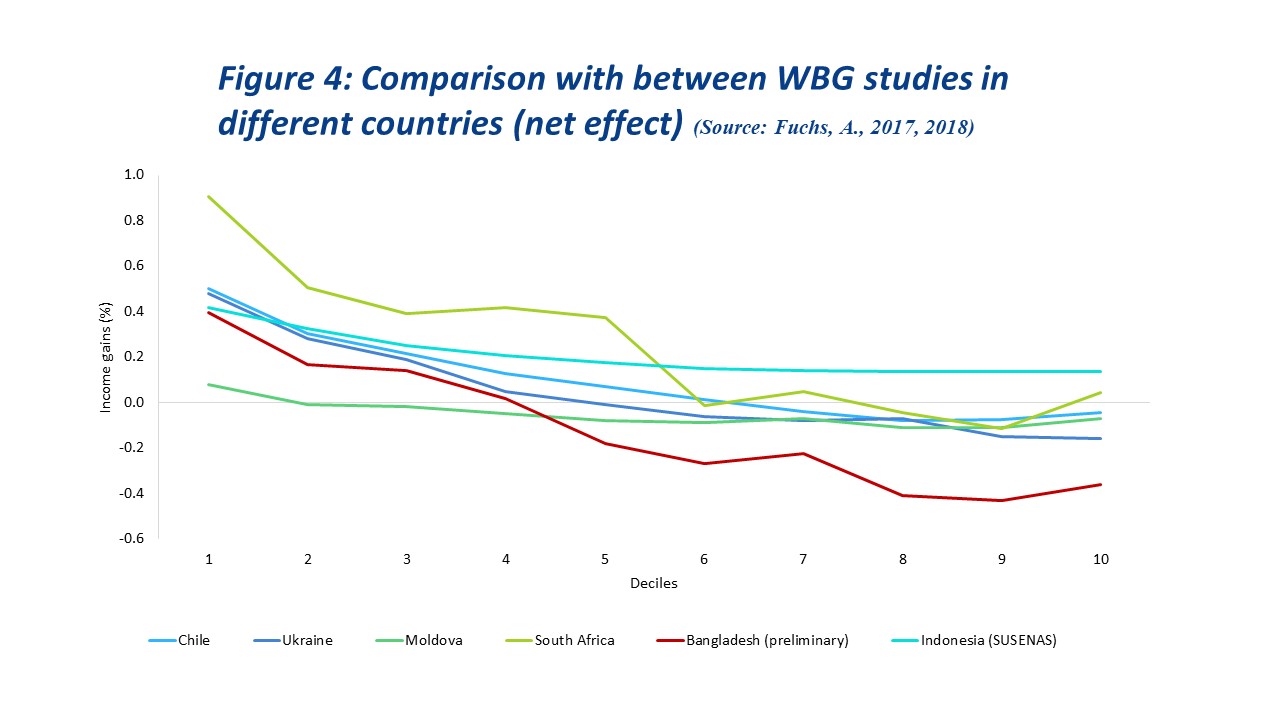

The net total distributional impact of tobacco taxation estimated in World Bank assessments done in in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chile, Moldova, Russia, South Africa, and Ukraine (Fuchs et al 2019), is shown in Figure 4. Lower medical expenditures and additional working years help offset the negative direct income effect of an increase in tobacco prices. The total income effect associated with a 25 percent price increase is positive in the case of several income groups, especially at the lower end of the income distribution. However, most households in Bangladesh and Indonesia, and between 30 and 50 percent of the population in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chile, and South Africa, continue to be negatively affected. In the particular case of Indonesia, the distribution continues to be U-shaped. The net effect becomes positive and more progressive with higher price increases, as reduce affordability of cigarettes allows the health and economic benefits of the taxes on tobacco to kick in. In a 100 percent price increase scenario, only the 40 percent richest households in Chile, and the top 60 percent in Bangladesh—where medical expenses have lowest incidence—are negatively affected. The results are generally progressive in all eight countries.

A most recent assessment done for Vietnam (Fuchs et al, 2019), confirms that above findings, as under moderate and to high price increase scenarios, the distribution of the net benefits is highly progressive. Poor households capture relatively large income gains that increase with the magnitude of the price increase. Increasing the excise tax, for example, by D 10,000 (US$0.43 cents) could bring income gains of over 1.5 percent to the poorest 30 percent of the population in Vietnam. The effect among the top four income deciles would be closer to zero under all scenarios.

In Tonga (Osornprasop 2019), the excise tax resulted in a price increase across all the taxed products, making cigarettes less affordable and affecting smokers’ behaviors. Tax on cigarettes has a greater effect on “less well-off” smokers, as a larger number of less well-off smokers reduced consumption of manufactured cigarettes. This is consistent with the other country findings on the equity impacts of price policies, as low-income households respond to price changes more readily than higher income households. Price, rather than other factors, was the main reason among those who decided to change behaviors and reduce consumption.

Assessing the situation in the United States, Furman (2017), concludes that the criticism against tobacco taxes is backward. The health benefits of tobacco taxes far exceed the increase in tax liability, and they accrue disproportionately to lower-income households. Moreover, as Furman observes, it is important to also evaluate what the additional revenue raised by the tobacco tax may be used for. The most recent increases in the United States, enacted in 1997 and 2009, were used to create and expand a very progressive children’s health insurance program.

Myth 3: Higher taxes lead to increased smuggling and use of counterfeit tobacco

Evidence: A recent global report by the World Bank Group focusing on over 30 countries across the income and development spectrum (Dutta et al, 2019), shows that, contrary to tobacco industry arguments, tobacco taxes and prices have only a limited impact on the illicit market share at the country level. The evidence presented in the report indicates that the illicit cigarette market is relatively larger in countries with low taxes and prices, while relatively smaller in countries with higher cigarette taxes and prices. Non-price factors such as governance status, weak regulatory framework, and the availability of informal distribution networks appear to be far more important factors. Countries reporting significant progress in the control of illicit tobacco trade adopted some key policy and institutional measures which contributed to their success.

A good example is Ireland, where a high rate of tobacco excise taxes, and the consequent high price of tobacco products, makes the country attractive to those involved in the illicit tobacco trade. However, Ireland’s comprehensive and effective system of customs and tax enforcement, alongside strong regulatory control of the tobacco market, has contained the illicit flow of tobacco products onto the Irish market. Indeed, Ireland’s most recent results indicate that the general trend for illicit cigarettes between 2007-2017 has been downward (13 presently). Notably, this has occurred during a period where price of cigarettes has risen and smoking prevalence has declined (by about 10 percentage points). This suggest that, while the illicit trade has not been eliminated, the extensive program of enforcement has contained it. Analysis indicates that the main driver of illicit flows is not relative levels of price/taxation, but the effectiveness of customs and tax enforcement.

A key lesson from the report’s country case studies is that strengthening the legal framework and tax administration and enforcement is complementary to tobacco tax policy reform as these measures reinforce one another. As outlined in the World Bank Group report, experience shows that illicit tobacco trade can be controlled by legal means (e.g., use of prominent tax stamps, serial numbers, special package markings, health warning labels in local languages, adoption of uniform tax rates nationwide that facilitate successful collection at the points of manufacture and import), and by increased law enforcement (e.g., improving corporate auditing, better trace and tracking systems, and good governance).

Myth 4: Tobacco tax hikes lead to significant job losses

Evidence: Policymakers considering tobacco tax hikes are often concerned about negative impacts on employment. World Bank Group research provides fresh evidence from field studies and economic simulations focusing on Indonesia (Araujo et al 2018), one of the world’s largest tobacco producers. The results provide clearer understanding of the relationship between tobacco taxation and employment.

Tobacco manufacturing represents only a small share of Indonesia’s economy-wide employment (0.60 percent) and a relatively low percentage of jobs in the manufacturing sector (5.3 percent). This compares to the food (27.43 percent), garment (11.43 percent), and textile (7.90 percent) sectors. The productivity of tobacco manufacturing workers is also quite low relative to the productivity of workers in other comparable sectors. Indonesia’s tobacco manufacturing is geographically concentrated in East and Central Java (76 percent) and West Nusa Tenggara (18 percent). Only a few districts are substantially dependent on tobacco sector employment.

Most tobacco farmers and manufacturing workers rely only partially on tobacco income. Income from kretek rolling represents 43 percent of household income among kretek households on average. About three-quarters of tobacco-farming households derived less than 50 percent of their income from tobacco cultivation, and over half of clove farmers generate less than 20 percent of their household income from cloves.

Tobacco cultivation is not profitable for most farmers, and producing tobacco has high opportunity costs. This finding was mostly consistent across regions, type of tobacco grown, and whether the farmer was on contract to grow tobacco. Despite poor returns typically, farmers reported being drawn to the assured market, the better prospects for credit, and the potential to earn cash.

Economic simulations suggest that raising cigarette taxes by an average of 12 percent that increases cigarette prices by an average 5 percent and simplifying Indonesia’s cigarette tax structure to six tiers will reduce cigarette demand by 1.89 percent, increase government revenue by 6.41 percent, and reduce gross employment in the tobacco manufacturing sector by 0.43 percent. This represents a reduction of less than 3,000 tobacco manufacturing jobs, most of them in the handmade kretek industry (2,245 fewer jobs). Importantly, these estimates do not consider the creation of jobs in other sectors due to the shift in consumers’ spending away from tobacco (the net effect).

The estimated total household income loss from reduced employment in the handmade kretek industry amounts to a small fraction of 1 percent (0.16 percent) of the revenue gain that Indonesia will obtain by increasing cigarette taxes.

To sum up, higher taxes, yielding higher retail prices, will cut tobacco consumption and reduce economic losses due to health care costs and compromised productivity, with low-income groups benefiting more as discussed above. Aggressive tobacco tax hikes will generate additional revenue that can more than compensate for the income loss following a reduction in employment in the kretek industry.

Take-Away Message

The common claims used by interest groups to oppose tobacco tax increases, price hikes, and reductions in demand and use, are not supported nor borne out by accumulated country evidence. Improved data availability and further research are required for updating and expanding the global evidence base to confront these claims as they have become widely-held “myths” often accepted uncritically by government officials and stakeholders, as well as the general public.

So, as stated in an article in The Economist (2017), the take-away message for policy makers and other stakeholders around the world, should be unambiguously clear: "As the success in rich countries shows, there is no mystery about how to get people to stop smoking: a combination of taxes and public-health education does the job. This makes the abysmal record in poor countries a grave failure of public policy. The good news is that, following recent research, it is one that has just become easier to put right."

By adopting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), countries across the world have committed to achieving a 30 percent reduction in death rates from noncommunicable diseases like cancer, stroke, and heart disease by 2030. Reducing tobacco use is critical for countries to reach this goal. To swiftly cut smoking rates, bold increases in tobacco excise tax rates are by far the most powerful tool.

High smoking prevalence condemns large numbers of people to avoidable sickness and death and weakens the country’s economic development. As observed by Jha and Peto (2014), attainment of the SDG target requires decreases not only in high-income countries but also in populous low- and middle-income countries “to prevent several tens of millions of tobacco- attributable deaths during the next few decades, and about 200 million tobacco-attributable deaths during the century as a whole, mostly among people who are already alive, both by helping smokers to quit and by helping adolescents not to start.”