The High Public Health and Economic Toll of Violent Crime in the Caribbean

Patricio V Marquez

February 5, 2025

“This gathering of broken pieces is the care and pain of the Antilles, and if the pieces are disparate, ill-fitting, they contain more pain than their original sculpture, those icons and sacred vessels taken for granted in their ancestral places.”

---Sir Derek Walcott, Saint Lucian poet and playwright, 1992 Nobel Laureate in Literature

“The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory”, Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1992

I. Introduction

Reading Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude, one is confronted with an unsettling reality: In the mythical town of Macondo, in Colombia’s Caribbean coast, violence has long been an accepted way of settling disputes between individuals and rival groups. While bloodshed may bring conflicts to a close, it leaves behind pain and sorrow, haunting the memories of the townspeople for generations. This lingering grief fuels an endless cycle of vengeance and violence.

While “magic realism” is at the core of García Márquez’s novel, its depiction of violence and its after-effects was shaped by historical events in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)—events that continue today, illustrating the inexorable reality of violence and its negative impact on families and communities everywhere.

As violence, in its various forms—interpersonal, self-directed, and collective—often results in premature death, physical and mental impairments, and lasting disability, it is a significant public health issue that imposes a heavy economic toll on societies worldwide.

Here, as recently discussed with colleagues from the Center for Health Economics at The University of the West Indies, where I serve as an Honorary Professor, I delve into this issue in LAC, with a particular focus on the current situation in the Caribbean region.

II. Violence as a Global Public Health Issue

Violence, as defined in the World Health Organization's (WHO)’s World Report on Violence and Health, is “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation."

WHO categorized violence into three main types:

• Self-Directed Violence: It occurs when the perpetrator and the victim are the same person (e.g., self-abuse and suicide).

• Interpersonal Violence: Involves violence between individuals, including:

- Family and Intimate Partner Violence (e.g., child abuse, violence by an intimate partner, and elder abuse); and,

- Community Violence (youth violence, rape or sexual assault by strangers, violence related to crimes, violence in institutional settings).

• Collective Violence: Committed by larger groups and categorized into social, political, and economic violence.

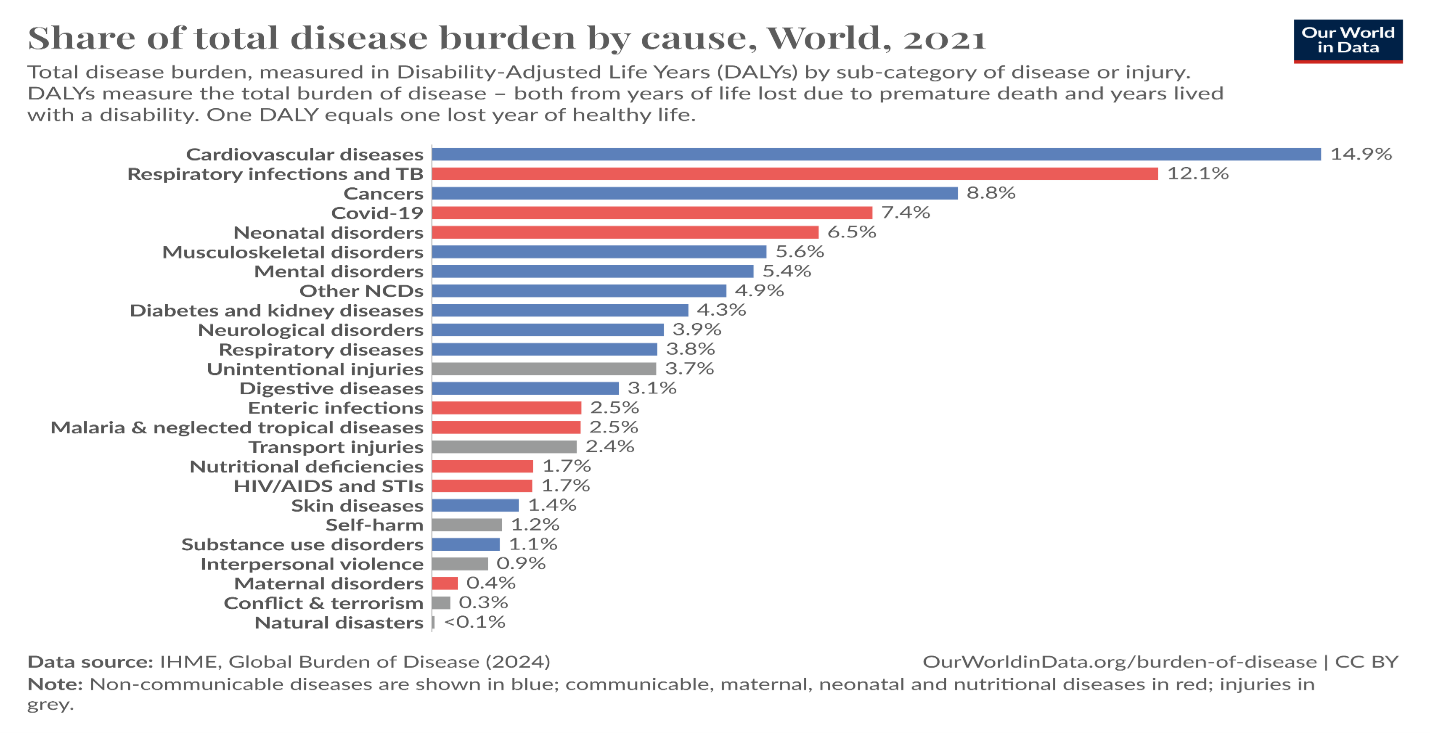

Data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) show that violence is a significant contributor to premature mortality and disability globally. In 2021, as shown in Figure 1, the disease burden attributable to all forms of violence was 2.4 percent of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2021.

Self-harm resulted in 33.53 million DALYs lost, while interpersonal violence accounted for 26.83 million DALYs lost, and conflict and terrorism contributed to 8.73 million DALYs lost.

Self-harm and interpersonal violence ranked among the 30 leadings causes of DALYs lost in 2021. DALYs measure the total burden of disease by combining years of life lost with years lived with disability, with one DALY representing the loss of one year of healthy life.

Figure 1:

III. Violent Crime and Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean Region (LAC)

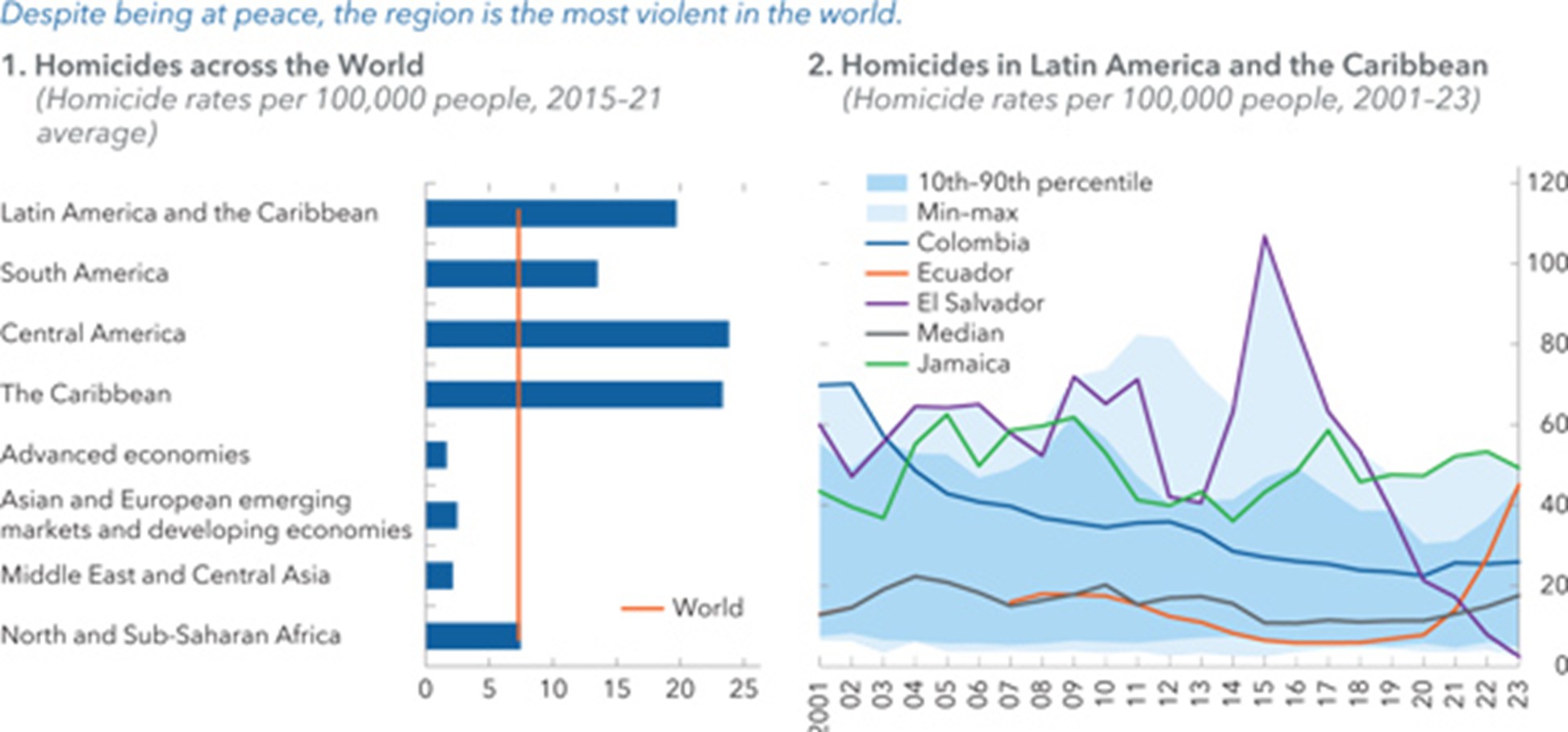

As documented in a 2024 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report, LAC is the most violent region globally. Despite comprising only 8 percent of the world’s population, it accounts for 29 percent of all homicides—approximately 130,000 annually. Over the past decade, as shown in Figure 2, panel 1, LAC's murder rate has been nearly 12 times higher than in advanced economies, 8 times that of emerging markets, and about 3 times the global average. The region is home to 8 of the world’s 10 most violent countries and 40 of the 50 most dangerous cities. In some countries, there have been important variations over time as shown in Figure 2, panel 2.

Figure 2: Crime and Violence in LAC

Source: Adopted from IMF (2024), “Violent Crime and Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Macroeconomic Perspective”. Sources: Igarapé Institute; official sources; UN Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (2023e); and IMF staff calculations. Note: For panel 2, the 10th-90th percentile range includes between 11 and 16 countries over the period, depending on data availability.

IV. The Caribbean is the most affected subregion

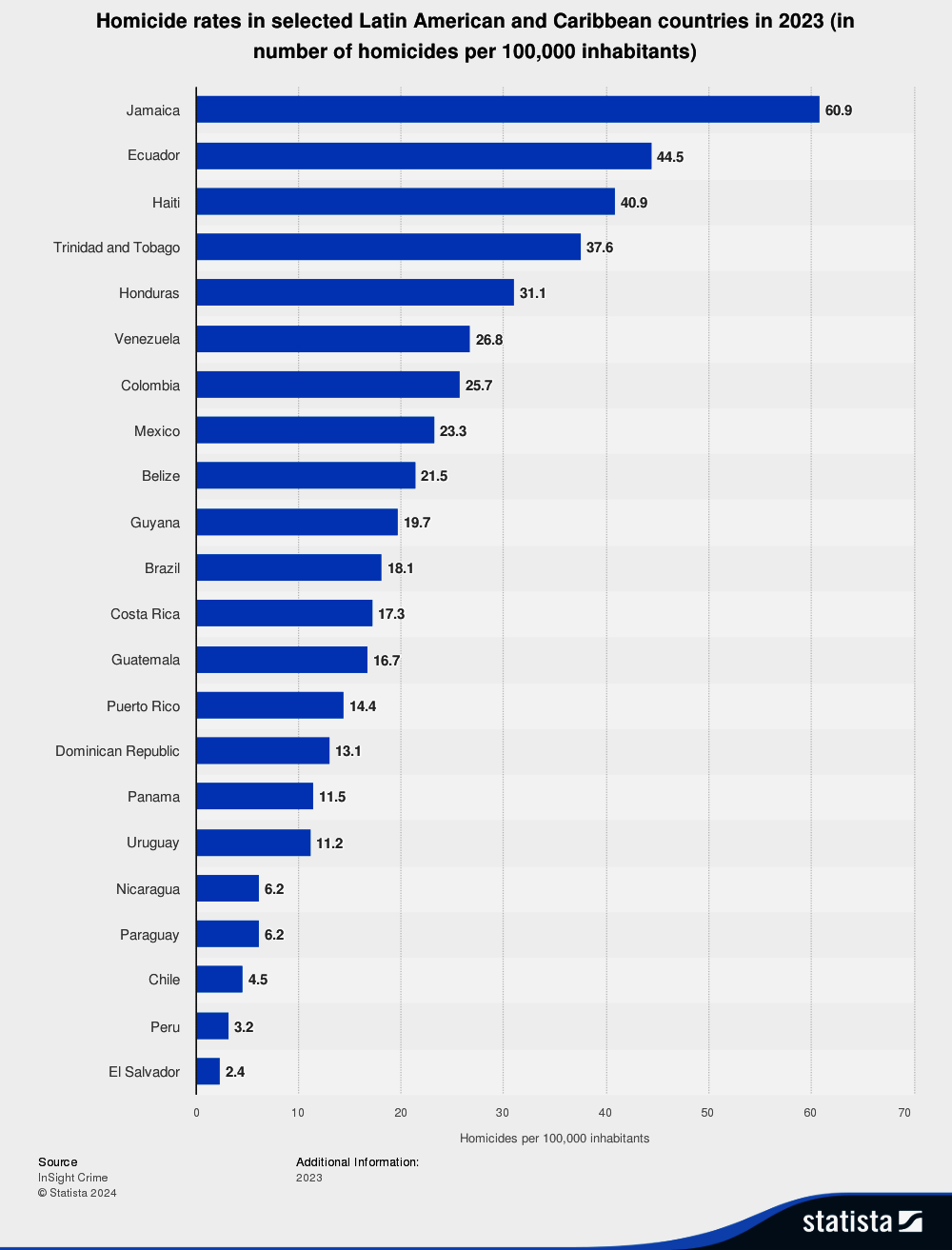

The countries in the Caribbean have some of the highest rates of violence in the world. While the homicide rate in this subregion declined by 19 percent over the past decade, data from 2021–2022 reveal sharp increases in some countries, with rates exceeding 30 per 100,000, more than five times the rate observed globally (5.6 per 100,000 inhabitants).

As shown in Figure 3 below, within the Caribbean, in 2023, some countries such as Jamaica (60.9 per 100,000), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (50.1 per 100,000), St Lucia (41.7 per 100,000), Haiti (40.9 per 100,000), and Trinidad and Tobago (37.6 per 100,000), exhibited alarmingly high homicide rates and highlight the urgency of addressing violent crime in the subregion.

Figure 3:

V. The Roots of Violence in LAC

As noted in the above-mentioned 2024 IMF report, violence in LAC is not just a law enforcement issue but also a socio-economic challenge. The region's deep-rooted violence is shaped by historical, economic, social, and political factors that have intersected over time, as follows:

- Historical Factors. Since colonial times, layers of violence—political conflicts, civil wars, slavery, and systemic discrimination—have reinforced each other, creating an enduring legacy of instability. State repression, corruption, and weak rule of law have further exacerbated crime by limiting the effectiveness of justice systems. This historical trajectory has allowed organized crime to flourish, particularly in regions where governments have struggled to maintain control.

- Economic Conditions. The IMF report suggests that structural economic challenges, including heavy reliance on extractive industries, weak governance, poverty, and inequality, have both contributed to and been worsened by violence. LAC remains the most unequal region in the world, with the wealthiest 10 percent earning 22 times more than the poorest 10 percent, a disparity twice as large as that of advanced economies. This extreme income inequality and wealth concentration correlates strongly with elevated levels of violence, as economic hardship and social exclusion push many individuals toward illicit activities, such as drug trafficking and extortion, to make a living and survive.

- Organized Crime. Drug cartels and transnational criminal networks play a central role in perpetuating instability. In many LAC countries, the interplay between drug cartels, armed groups, and both public and private actors have entrenched criminal governance while weakening state authority. The lucrative drug trade, human trafficking, and illegal arms smuggling thrive in regions where law enforcement is underfunded, corrupt, or overwhelmed by the scale of the problem. The IMF report further notes that criminal organizations fill governance gaps in marginalized communities, providing employment and social services in exchange for loyalty, making them difficult to dismantle.

- Geographical Factors. Certain border regions, transportation hubs, and densely populated urban slums serve as crime hotspots, where limited state presence and porous borders facilitate smuggling operations and human trafficking. Additionally, unresolved land disputes and resource conflicts between indigenous populations and corporate interests have fueled mass protests and, in some cases, violent confrontations. Weak infrastructure and inadequate policing make these areas particularly susceptible to criminal activity and organized violence.

- Social Development Challenges. The marginalization of indigenous populations, inadequate education systems and vocational training, and high levels of youth unemployment further drive crime rates. Poor access to quality education and training, combined with limited formal job opportunities, leaves many young people vulnerable to recruitment by gangs and criminal organizations.

VI. Organized Crime, Drug Trafficking, and Gang Violence in the Caribbean

As documented by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in the Caribbean, drug trafficking by organized crime has been associated with record homicide levels, corruption, democratic backsliding, and money laundering, among other negative impacts. It has also prompted wars between gangs over the control of criminal economies, expanded illegal firearms trafficking, and exacerbated human trafficking both within the region and beyond.

While drug transshipment through the Caribbean is not new, the region has faced renewed challenges, with large-scale trafficking due to rising European demand.

Among the countries that play a significant role in transshipping cocaine through the Caribbean are the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Suriname. Cocaine, primarily grown in Colombia, is trafficked through Venezuela before being transported by go-fast boats to the Dominican Republic, either directly or by island-hopping through Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Martinique, and St. Kitts and Nevis. While Spain has traditionally been the main European destination due to linguistic ties, Dutch authorities have recently reported increasing connections between Dominican and Dutch criminal networks.

The Caribbean has also seen a significant increase in the extent and intensity of gang violence in 2022, as observed in countries such the Turks and Caicos Islands, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, the Bahamas, and Haiti.

Trinidad and Tobago, in particular, has reported a dramatic rise in violent crime, with murders increasing from 97 in 1998 to 623 in 2024, translating to a rate of 37.6 per 100,000 residents. Nearly 50 percent of violent crimes are linked to organized criminal groups, surpassing the per capita murder rates of Mexico and Colombia, ranking the country as the sixth most dangerous worldwide. Despite government efforts to combat organized crime, murder, robbery, and corruption have escalated.

VII. The Role of Firearms in Homicides

A 2023 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime pointed out that access to and misuse of firearms is a key factor contributing to the disproportionately high rates of lethal violence in the Caribbean. Unlike bladed weapons or blunt objects, firearms significantly escalate both the speed and scale of intentional and unintentional killings. In 2021, firearms were involved in 67 percent of homicides in the Caribbean.

Disaggregated data presented in another report show that Jamaica, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, the Bahamas, and Belize are among the countries with the highest percentages of firearms-related homicides at 90, 84, 78, and 75, and 66 per cent of total homicides, respectively.

In the Caribbean, as in the broader LAC region, firearms often originate from foreign sources, particularly North America and Western Europe, through both legal and illegal channels. The "iron pipeline," a trafficking network from the United States to the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, has garnered increasing attention. This issue was underscored in the 2023 War on Guns declaration by the heads of government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

Besides firearm availability, the region faces additional challenges, including weak oversight, insufficient control measures, and widespread impunity.

VIII. Demographics, Violence, and Alcohol and Substance Use in the Caribbean

Young men (ages 15-29) in the Caribbean are disproportionately both victims and perpetrators of homicide, often drawn into criminal organizations due to poverty, limited education, and lack of employment opportunities.

The above trend aligns with broader patterns of youth delinquency in the English-speaking Caribbean. A study assessing self-reported delinquency—including involvement in violence, property offenses, alcohol and marijuana use, drug sales, and gang activities—found that youth disproportionately engage in violence. Alcohol use and property crime was the next most frequent form of self-reported delinquency. Self-reported marijuana use was also significantly different between nations. The findings of the study also revealed that a high proportion of Caribbean youth are gang-involved. Self-reported delinquency was consistently higher among males than females for every offense type, although a substantial proportion of females were involved in a wide range of offending.

IX. Gender-based Violence

The killing of women and girls by intimate partners and other family members is an indicator for gender-related killing of women and girls, also known as "femicide/ feminicide". Women comprise 54 percent of victims in domestic homicides and 66 percent of those killed by an intimate partner. In LAC, in particular, women and girls are significantly more likely to be killed by intimate partners than by other family members, whereas the shares of female intimate partner and family-related homicides tend to be more equal in countries in other regions.

As reveled in a recent study, violence against women remains widespread across the Caribbean, with sexual coercion and abuse being significant concerns.

Findings of national surveys conducted between 2016 and 2019 in five CARICOM Member States—Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago—to assess the prevalence of gender-based violence revealed that, on average, 46 percent of ever-partnered women aged 15-64 had experienced at least one form of intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetime—physical, sexual, psychological, or economic. Additionally, 14 percent had experienced at least one of the three current forms of IPV (physical, sexual, or psychological). Lifetime IPV prevalence rates varied by country, ranging from 55 percent in Guyana to 39 percent in Grenada and Jamaica. These findings underscore how gender inequality and entrenched norms of male dominance in relationships contribute to the ongoing risks women face at home and in their communities. A culture of silence and victim-blaming further exacerbates the problem, creating stigma and barriers for survivors seeking support.

In the Caribbean, no country has comprehensive laws addressing gender-based violence, including femicide or feminicide. The continued prevalence of violence against women underscores the urgent need for stronger enforcement, comprehensive legal frameworks, and targeted interventions to address this entrenched issue.

X. Direct Economic Cost of Crime and Violence

As noted in a 2024 study done by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), high levels of crime and violence in LAC significantly hinder sustainable economic growth, the reduction of poverty and inequality, and combating climate change. The data revealed that the direct costs of crime and violence in the region reached 3.44 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2022, a figure largely unchanged from previous years. The Caribbean had the highest costs (3.83 percent), as compared to Central America (3.46 percent), the Andean Region (3.22 percent), and the Southern Cone (3.2 percent).

This economic burden equates to nearly 80 percent of public education budgets, twice the spending on social assistance, and twelve times the investment in research and development.

The direct costs estimated in the study include:

- Human Capital (0.76 percent of GDP): loss of economic potential due to homicides, reduced productivity from non-lethal crimes, and the diminished productive capacity resulting from incarceration. In the Caribbean, this value was 0.99 percent of GDP in 2022, an increase over 2014 (0.89 percent of GDP), that is higher than in Central America (0.78 percent of GDP), in the Andean Region (0.64 percent of GDP), and the Southern Cone (0.60 percent of GDP). The relative share of the cost of homicides in the Caribbean represented 72 percent of the direct cost in human capital.

- Public Sector (1.08 percent of GDP): Government expenditure on security and justice systems related to crime prevention and response, including costs in police services, justice administration and prison administration). In 2022, the Caribbean had the highest average direct cost to the public sector, amounting to 1.24 percent of GDP in 2022, as compared to the Southern Cone (1.17 percent), Central America (1.03 percent), and the Andean Region (0.86 percent). As cited in another report, study research in the Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica also reveals that firearm-related violence imposes a significant medical care cost, as the average medical expenditure for treating a single gunshot wound exceed the annual health spending per capita by ratios ranging from 2:1 to 11:1. The allocation of public funds for crime prevention and response activities has a significant opportunity cost as these funds could be used to address other needs and enhance social welfare.

- Private Sector (1.6 percent GDP): Spending by businesses on security measures to protect their operations and assets. In 2022, the Andean Region (1.72 percent of GDP) and Central America (1.65 percent) were the regions where the average direct cost to the private sector was highest, while in the Caribbean, the average cost was 1.6 percent of GDP, and it the Southern Cone, it was 1.43 percent of GDP.

XI. Indirect Economic Cost of Crime and Violence

As suggested by the IDB study, to fully grasp the economic burden of crime and violence, it is essential to consider not only direct costs but also indirect ones, which significantly impact multiple sectors and hinder long-term development of LAC countries. Crime and violence not only disrupt businesses and discourage investment but also negatively impacts tourism, productivity, and migration patterns.

Rising homicide rates deter tourists, leading to declines in visitor arrivals and harming local economies reliant on tourism revenue, particularly in the Caribbean. Businesses operating in insecure environments experience lower productivity, declining sales, and increased closure risks. High homicide rates drive increased emigration, resulting in a loss of human capital.

Additionally, the labor market is constrained by reduced job opportunities and lower wages, while education systems struggle with higher dropout rates and poor academic performance. Public health declines due to violence-related physical and mental health issues, particularly among victims of gender-based violence. Ultimately, crime and violence erode social trust, weakens community resilience, and contributes to environmental degradation.

XII. The Impact of Crime and Violence on Economic Growth

Estimates from the IMF indicate that violent crime significantly hampers economic growth and private sector development in LAC by discouraging investment, reducing productivity, and increasing business costs.

Municipal-level data show that a 10 percent increase in homicides results in a 4 percent decline in economic activity. IMF projections suggest that cutting homicide rates in half could boost local economies by an average of 30 percent, though national-level impacts may be smaller due to shifts in economic activity. Additionally, spikes in crime can quickly contract production, with a 10-percentage-point rise in crime-related news coverage linked to a 2.5 percent drop in industrial production within three quarters.

Previous research by the World Bank Group showed that in six LAC countries, the estimated cost of violence was 8 percent of GDP; a 10 percent reduction in violence would lead to a one percentage point increase in annual economic growth in the two most violent countries.

XIII. A Comprehensive Approach to Crime and Violence Reduction

Investment in crime and violence reduction in the LAC region is critical for the economic and social development of countries. A 2016 World Bank Group report emphasizes the importance of prevention as a policy priority and highlighted the need for evidence-based policy design. A comprehensive, cross-sectoral policy approach that combines context-specific interventions is required to address the broad and diverse factors driving violent crime. Based on an initial review of available literature, a set of specific policies is presented below.

1. Data and Analytics for Crime Surveillance

Accurate and timely crime data are crucial for informed policymaking, monitoring, and evaluation. Since crime tends to concentrate in specific vulnerable areas, the collection of local data enables tailored public safety solutions that effectively address community-specific crime challenges. Strengthening data-sharing among governments, international organizations, and civil society can further support evidence-based policymaking.

International best practices demonstrate that interpersonal violence and its social consequences can be prevented by addressing root causes. For decades, Cali, Colombia’s third-largest city, ranked among Latin America’s most dangerous, with low-income communities particularly affected by conflict, distrust in public institutions, and "invisible borders" created by drug trafficking, limiting access to schools and jobs.

In the mid-1990s, the Cali municipal government—working with a university research center, the police, and judicial agencies—collected data and analyzed homicide patterns finding that most occurred on weekends, holidays, and paydays. Data also revealed that 30 percent of victims were intoxicated, and 80 percent were killed by firearms. In response, the city launched the Development, Security and Peace Program, or Desepaz, to address key risk factors. The initiative included restrictions on alcohol sales, prohibiting restaurants, bars, and discos from serving alcohol after 1 a.m. on weekdays and 2 a.m. on weekends. Additionally, firearm restrictions became a central component, as guns were involved in 90 percent of Cali’s murders. Although the army, which manufactures and sells firearms, initially resisted the policy, it was ultimately convinced by strong data demonstrating the benefits of limiting civilian firearm use.

In 2015, Cali joined the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities initiative. Through citizen engagement--including focus groups and workshops—the city gained deeper insights into chronic challenges and refined its resilience strategy. This led to the creation of the Secretariat of Peace and Civic Culture, tasked with designing violence prevention policies, promoting peaceful conflict resolution, and fostering a culture of peace. Additionally, Civic Culture Roundtables (Mesas de Cultura Ciudadana) were established to involve communities in addressing local safety concerns.

These efforts have yielded significant results: By 2017, Cali’s murder rate dropped to its lowest in 25 years—51.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, down from 93 per 100,000 in 1992. Furthermore, public trust in institutions improved in participating neighborhoods, demonstrating the power of data-driven, community-focused interventions in reducing violence.

2. Economic and Social Policies for Crime Prevention

Sustained economic growth, job creation, and domestic resource mobilization are essential for crime and violence prevention. Macroeconomic stability contributes to job creation and to expand employment opportunities among the youth, lowering unemployment rates and financial stress, and reducing gang affiliation and violent crime leading to improved public safety. Additionally, strengthened rule of law and anti-corruption efforts in countries are key measures for supporting economic growth and sustain crime prevention efforts.

Expanding the tax base and improving tax administration enhance fiscal capacity, facilitating sustained funding for targeted social programs such as quality education and vocational training, and law enforcement. Taxation on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages are effective but underused policies of disease prevention and health promotion, that could also help mobilize additional government revenue to fund investments and programs that benefit the entire population and enhance equity.

3. Effective and Accountable Criminal Justice Institutions

the ability of the LAC region to combat violent crime is hindered by inefficiencies in the criminal justice system. For instance, out of every 10 homicides, only about 4 suspects are formally processed, and fewer than two are convicted. In contrast, Europe convicts suspects in 8 out of 10 homicide cases, and Asia convicts 6. High levels of impunity in LAC stem from difficulties in investigating gang-related homicides and challenges in securing witness cooperation.

Stronger gun laws are essential to reducing violent crime, mass shootings, and police fatalities by limiting firearm access, enforcing licensing requirements, and holding manufacturers accountable. This is a critical policy action, as the experience in the United States shows that states with weaker gun laws experience higher homicide rates, more frequent mass shootings, and increased police officer fatalities compared to those with stronger regulations. Effective cooperation among law enforcement agencies at all levels, along with international collaboration, is essential for enforcing firearms laws, combating organized crime, and disrupting illicit trafficking.

The LAC region requires well-funded and operationally effective police and judiciary systems, safeguarded against corruption and criminal infiltration. However, as seen in Trinidad and Tobago, governments have long struggled with widespread corruption and resource constraints, hindering efforts to combat organized crime. Despite multiple States of Emergency in the past five years, security operations have had only moderate success in seizing illegal weapons and contraband. Criminal activity remains deeply embedded in the economy, making large-scale crackdowns difficult without affecting non-gang members.

Enhancing public trust is critical to improving crime reporting and reducing impunity. A study in Trinidad and Tobago reveled that while violent crime surged over the past two decades— with the murder rate increasing by 475 percent from 1999 to 2016—police efforts remained largely ineffective, with an annual homicide clearance rate of just 76 cases. Interviews in high-crime, low-income communities further suggest that institutional distrust discourages residents from cooperating with law enforcement.

Leveraging new technologies for crime prevention, such as predictive policing—which utilizes computer systems to analyze large datasets, including historical crime data—to guide police deployment and identify individuals who may be more likely to commit or become victims of crime, along with digital surveillance tools, can enhance law enforcement efficiency.

4. Community-Based Interventions

Lack of public and private investment in low-income communities contribute to physical decay, including vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and urban blight—conditions strongly linked to higher crime rates, particularly gun violence. The Broken Windows Theory, developed by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, suggests that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows, graffiti, and litter, can foster an environment that encourages more serious crime by signaling a lack of social control and community care.

Addressing these forms of disorder promptly is believed to help prevent more significant criminal activity. Studies from the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University have found a 13 percent reduction in gun assaults after repairing broken windows and maintaining abandoned properties. Additionally, community initiatives that actively engage residents—such as cleaning and greening efforts, which transform vacant lots into parks and green spaces, help reduce crime by alleviating stress, fostering social connections, and eliminating environments that facilitate illegal activities. Enhancing street lighting in high-crime areas further strengthens public safety. To sustain these efforts, central and local governments must prioritize funding for the revitalization of disinvested neighborhoods, fostering safer, more connected communities.

Community-violence intervention (CVI) programs, such as Cure Violence initiatives adopted in several cities of the United States, aim to reduce homicides and shootings by building trusted partnerships among community stakeholders, at-risk individuals, and government agencies. These programs connect individuals with credible community members who offer guidance and support, promoting nonviolent conflict resolution. Cities like Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago have reported over a 30 percent reduction in shootings and killings, while Oakland, California, achieved a 50 percent decrease in gun violence over seven years.

As highlighted in a 2016 World Bank Group report, adolescence and young adulthood are crucial developmental stages characterized by reduced parental control, increased peer influence, and transitions to adult roles, such as entering the workforce. These phases are particularly challenging for young people from low socioeconomic backgrounds, who face a higher risk of school dropout. Additionally, significant brain development occurs during this time, influencing self-control, risk-taking, and decision-making. The heightened sensitivity to peer-related rewards further increases the likelihood of risky behaviors.

Schools, therefore, can play a critical role in preventing youth involvement in crime by fostering students' physical and emotional well-being through social and emotional learning and restorative discipline practices—such as mediation and conflict resolution—that empower students and prevent conflicts from escalating into violence.

Programs that support the positive development of young people also contribute to improving public safety by addressing underlying risk factors such as poverty, trauma, and lack of education. Given that young people are particularly vulnerable to impulsive behavior and peer pressure, interventions that teach decision-making and cognitive behavioral skills have demonstrated significant success. For example, programs in Chicago, that provide group sessions for young men from disadvantaged neighborhoods, have led to a 45–50 percent reduction in violent crime arrests and increased high school graduation rates.

5. Mental Health and Substance Use Programs

The Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) has identified violence as a major public health issue in the region, significantly impacting physical, mental, and psychosocial health while straining health systems and incurring substantial economic and social costs.

Although most individuals with psychotic disorders will never commit violence, research indicates that the risk is higher among those with schizophrenia compared to the general population, particularly during the first episode of psychosis. Studies also show that schizophrenia is linked to the highest rate of homicide, whereas mood and anxiety disorders have the lowest. Multiple factors, including childhood abuse, prior violent behavior, substance abuse, homelessness, unemployment, and divorce, influence the connection between mental illness and homicide.

The above findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive mental health care and support systems to reduce risks and safeguard both individuals and the broader community. Expanding access to mental health services and addiction treatment is essential in addressing factors linked to violence. Integrated programs that provide counseling, treatment, rehabilitation, and community-based support can help mitigate the impact of mental health issues and substance abuse on violent behavior while reducing stigma and improving accessibility.

Houston's One Safe Houston initiative exemplifies this approach by integrating public health-focused programs alongside law enforcement efforts to tackle crime's root causes. These initiatives include community violence intervention programs like Cure Violence and Credible Messenger Mentoring, which engage individuals directly affected by violence to break cycles of gun violence. Domestic violence response teams, composed of officers and trauma-informed advocates, provide critical support, while culturally competent outreach strategies aim to disrupt domestic violence-driven homicides. Mental health interventions such as the Mobile Crisis Outreach Team and the Crisis Intervention Response Team ensure appropriate crisis response, allowing police to focus on serious crimes. Additionally, the Community Re-entry Network Program aids formerly incarcerated individuals with life skills, job readiness training, and connections to essential services, fostering safer and healthier communities.

XIV. Takeaways

The LAC region, particularly some Caribbean nations, continue to face high crime rates, including some of the highest homicide rates in the world. Violent crime leads to loss of life, a diminished quality of life, rising security costs for both governments and the private sector, and constrained economic activity.

As Carlos Felipe Jaramillo, the World Bank Group Vice-President for LAC, clearly pointed out in a recent article, since violence is at the core of the LAC region’s most pressing problems, it must be central to the conversations about economic growth, productivity, poverty, and inequality reduction.

Effectively addressing this challenge requires strong political commitment, resilient institutions, economic inclusion, adherence to the rule of law, and coordinated multisectoral action that target the long-term determinants of violent crime. These efforts must be guided by the systematic collection and use of context-specific data and information.

Without this foundation, countries risk remaining fragile and vulnerable, perhaps not for “100 years in solitude,” but long enough to see their development prospects undermined. Inaction in the face of this significant development challenge will lead to substantial human capital and economic losses, while also eroding social cohesion—intensifying fear and uncertainty in communities as people worry that a loved one could be the next victim of violence.

Source of Images:

Image 1: Fernando Botero's painting "IL Massacro: Ore 20.15" (2004)", picture taken by author at Exhibition "Fernando Botero La Grande Mostra", Roma, Palazzo Bonaparte, November 2, 2024.

Image 2: Shutterstock 387587290 "Handwritten graffiti No Guns sprayed on the wall".